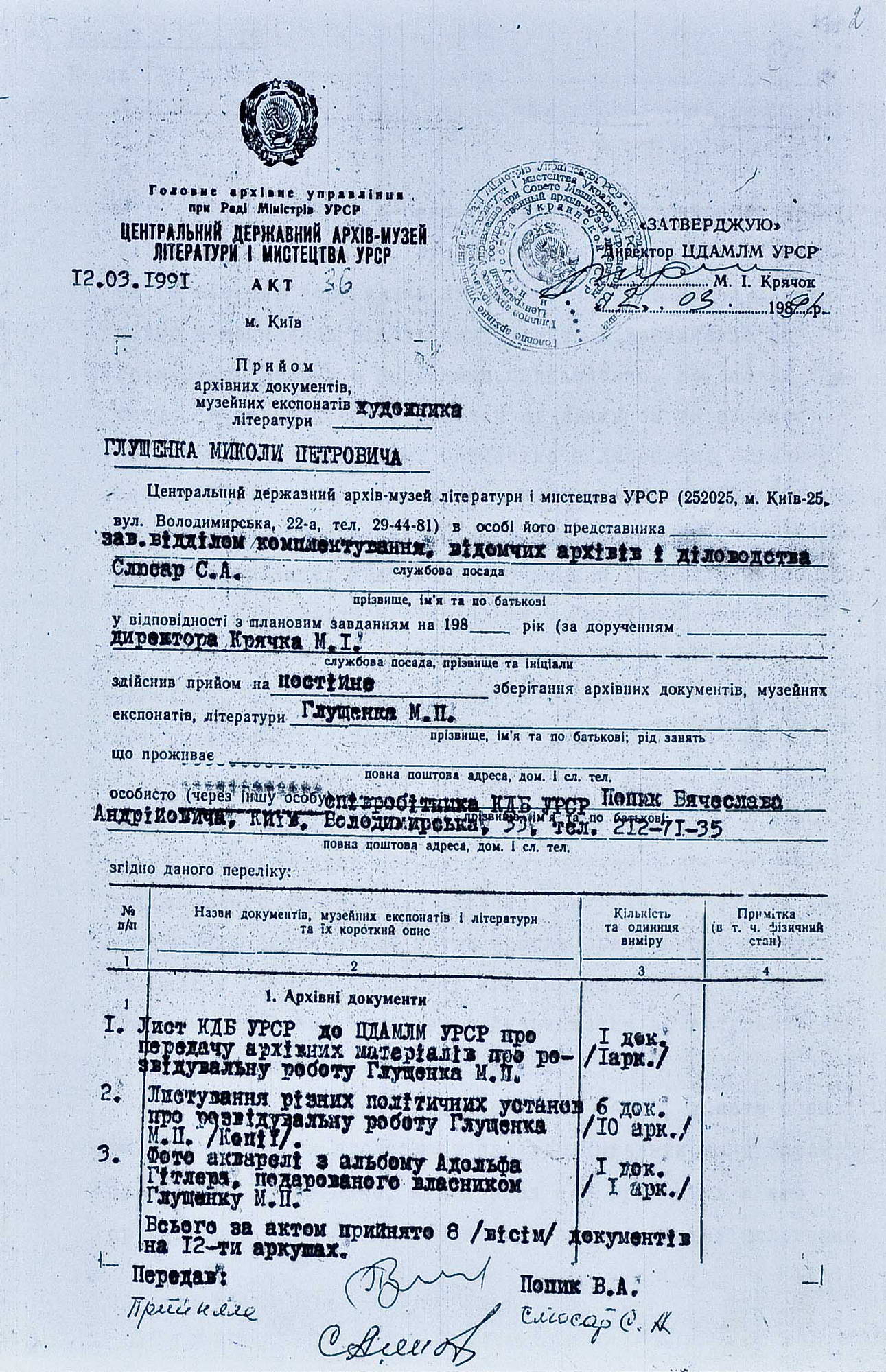

Mykola Hlushchenko

an artist, agent of Soviet secret services

1901

|

1977

Mykola Hlushchenko was born in Novomoskovsk, the Dnipropetrovsk region. He defined his origin as “peasant”. In 1918, Mykola joined Denikin’s army as a private, and was promoted to corporal later on. Together with the army, he retreated abroad and was interned in Poland. Then Hlushchenko moved to Germany, where he studied at the Academy of Arts in Berlin. Later on, he fled to France, and quickly became a popular artist there.

Despite such background, the artist managed to build a successful career. When Hlushchenko returned to the Soviet Union in the 1930s, they did not purge him, as was often the case, although there were plenty of reasons for that: friends among Ukrainian political migrants (Volodymyr Vynnychenko or Vasyl Vyshyvanyj) and connections with the highest ranks of the Third Reich.

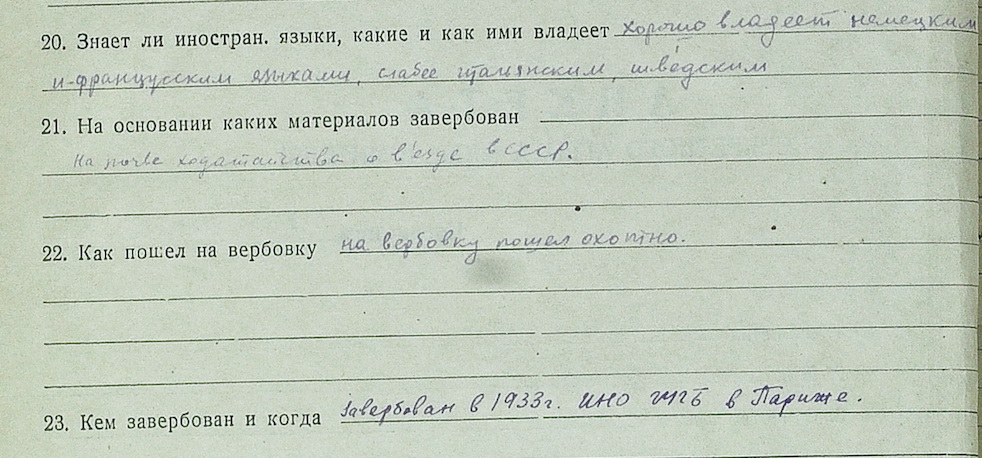

However, Hlushchenko was often sent on business trips abroad, could meet foreign nationals in the Soviet Union without restrictions, accompanied diplomatic missions, could easily send letters abroad and receive parcels with foreign books. The artist spoke German, French, Italian and Swedish.

Hlushchenko moved to Paris in 1925. When he was officially recruited in 1933, his paintings were already on display in salons of Berlin, Paris, Milan, Stockholm, Rome and other European cities. Secret services recognised his talent:

“[Hlushchenko] is regarded as the best Ukrainian artist; he has his own studio in 23 Rue des Volontaires. [..]”.

Despite a successful career in the West, the artist wanted to return home. One of the reasons stated during verification, was his mother, “a 50-year old woman, he is very attached and gives regular financial support to”.

In 1931, Hlushchenko wrote a letter offering to organise an exhibition of paintings of Ukrainian migrants living in Paris. In that letter to All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (VOKS), he also wrote about own exhibitions in various European cities and his numerous connections.

The Soviet intelligence was interested in that barely concealed proposal. They started checking a potential agent and found out that Hlushchenko was applying for entry to the USSR and had performed unofficial tasks before. “Hlushchenko has been long involved with our Consulate in Paris and has a Soviet passport”.

According to the intelligence, in the 1920s, Oleksandr Polotskyi, who worked in the Soviet consulate abroad, financially assisted migrant Hlushchenko. He also helped to publish Mykola’s articles and works in Ukrainian Soviet magazines. The support was suspended for a while, when it was found that Hlushchenko had chosen a Soviet course in his work “only because of financial rewards”.

Perhaps, that was the reason why the Foreign Department of the GPU (INO GPU), an agency responsible for foreign intelligence, initially had some doubts about the sincerity of his intentions. First documents of the agent file distrustfully name Hlushchenko, a member of the Parisian bohemia, a “migrant and Petliurist”, preferring “silk shirts”.

However, after careful checks, intelligence gave the green light to recruit an agent:

“Basing on the information gathered about Hlushchenko, we have come to conclusion that he is worth recruiting. There is evidence suggesting that negotiations with him might be successful. It shall be noted that Hlushchenko has close connections with Ukrainian migrants in Paris, while his frequent trips around Europe make it possible to call him to Berlin or another convenient place for further negotiations”.

After recruitment, Hlushchenko was still suspected of working for two services for some time: could Ukrainian nationalists recruit him to gather intelligence on the territory of the Soviet Union? There seemed to be reasons for such assumption: Hlushchenko had a lot of friends among Ukrainian migrants; and he was very keen to get permission to enter the USSR. That’s why he was not allowed to return for several years. According to GPU, he was of greater use abroad.

In 1935, Mykola Hlushchenko finally obtained a permission to return to the USSR. However, he had to face the Soviet bureaucracy straightaway: they forgot to issue a visa for his wife. Moreover, she was not even checked for reliability, and nobody was allowed to the USSR without verification.

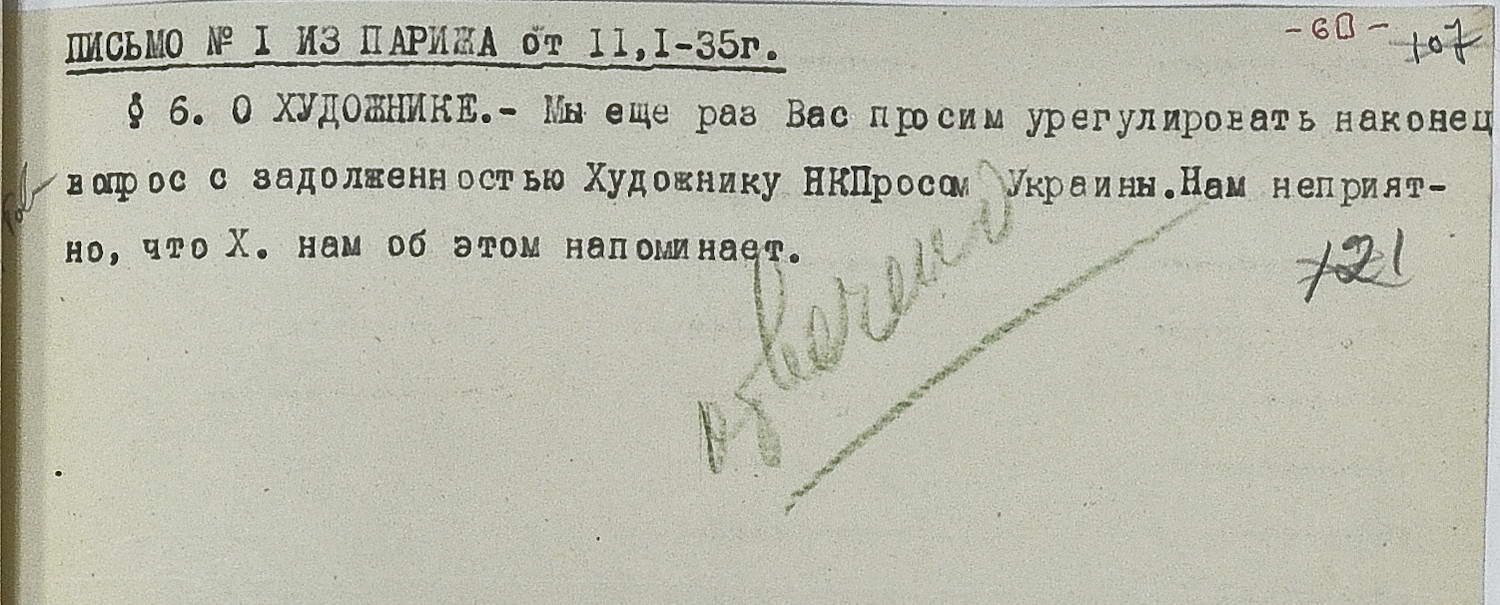

After the delay, Hlushchenko eventually returned to the Soviet Union in the midst of mass purges and repressions, which he indirectly experienced while being still abroad. For years, he asked the People's Commissariat for Education of the Ukrainian SSR to pay his mother a fee for an exhibition of paintings, and sought the GPU’s assistance. His request was passed from one department to another for a long time to find out what kind of fee, for which paintings was to be paid, as well as who had made a commitment and what kind of commitment that was:

6. As for the Artist. We hereby once again ask you to settle the issue of the debt of the People's Commissariat for Education of Ukraine to the Artist. We do not like being reminded about this issue by the Artist”.

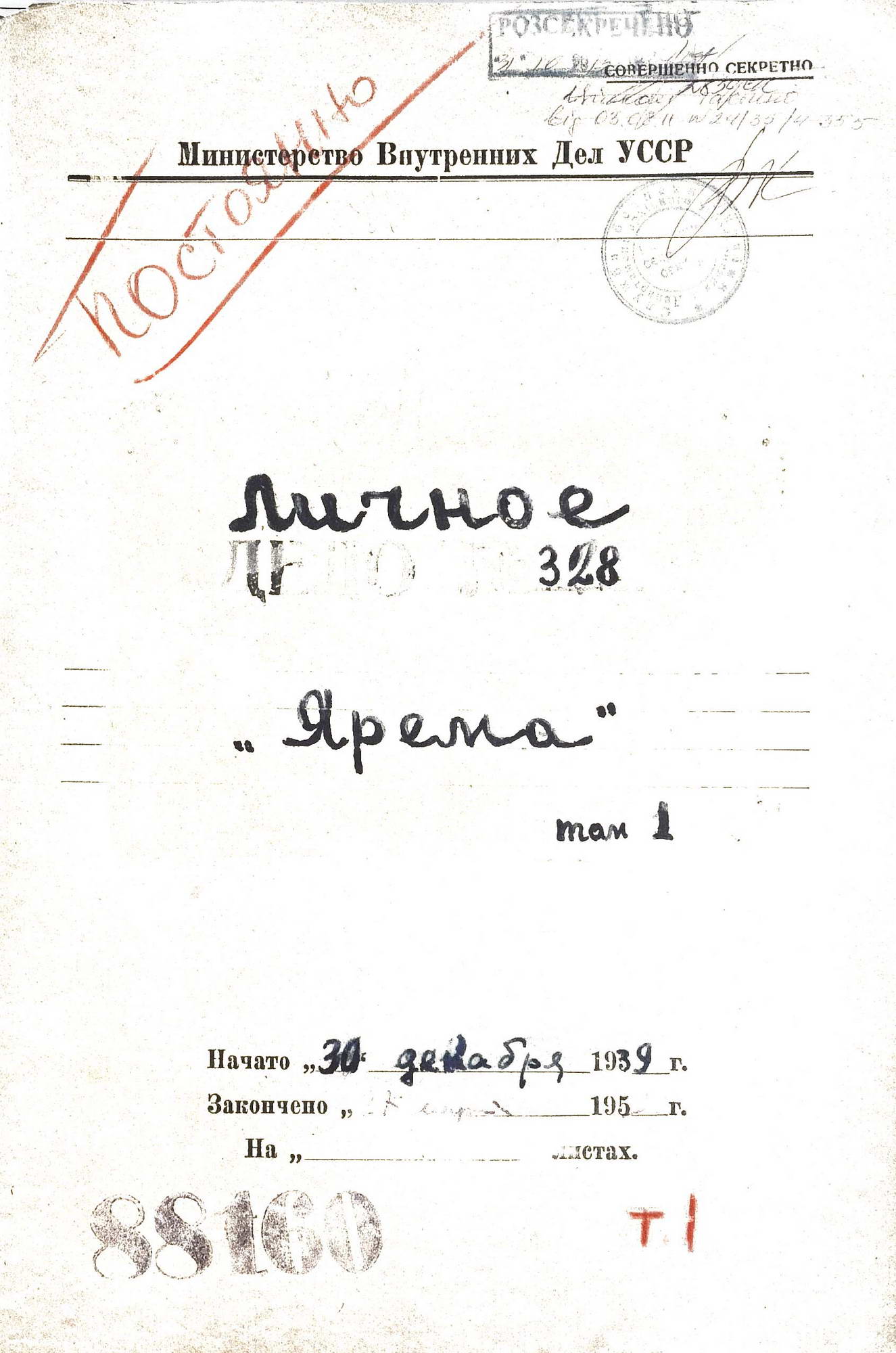

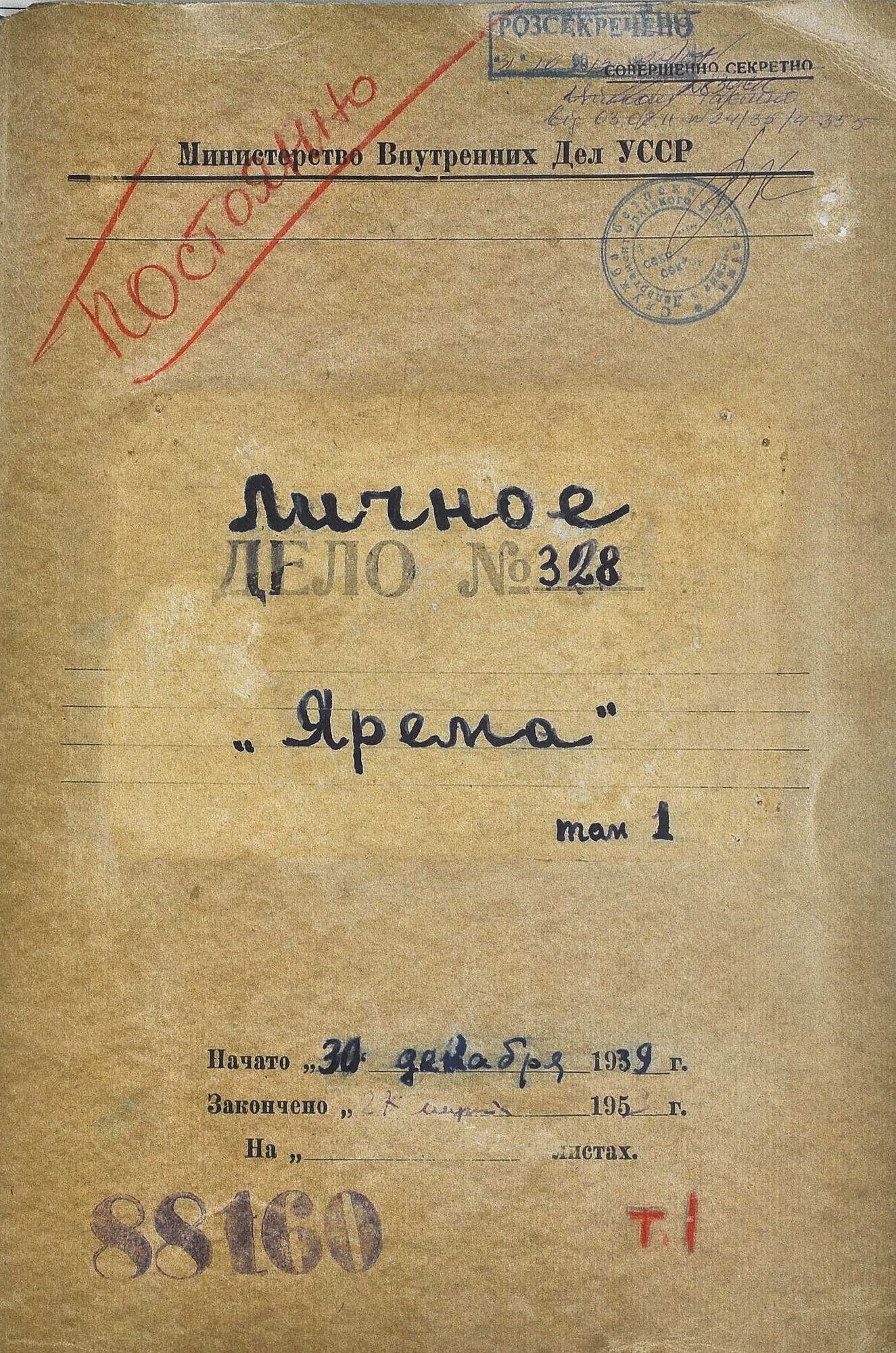

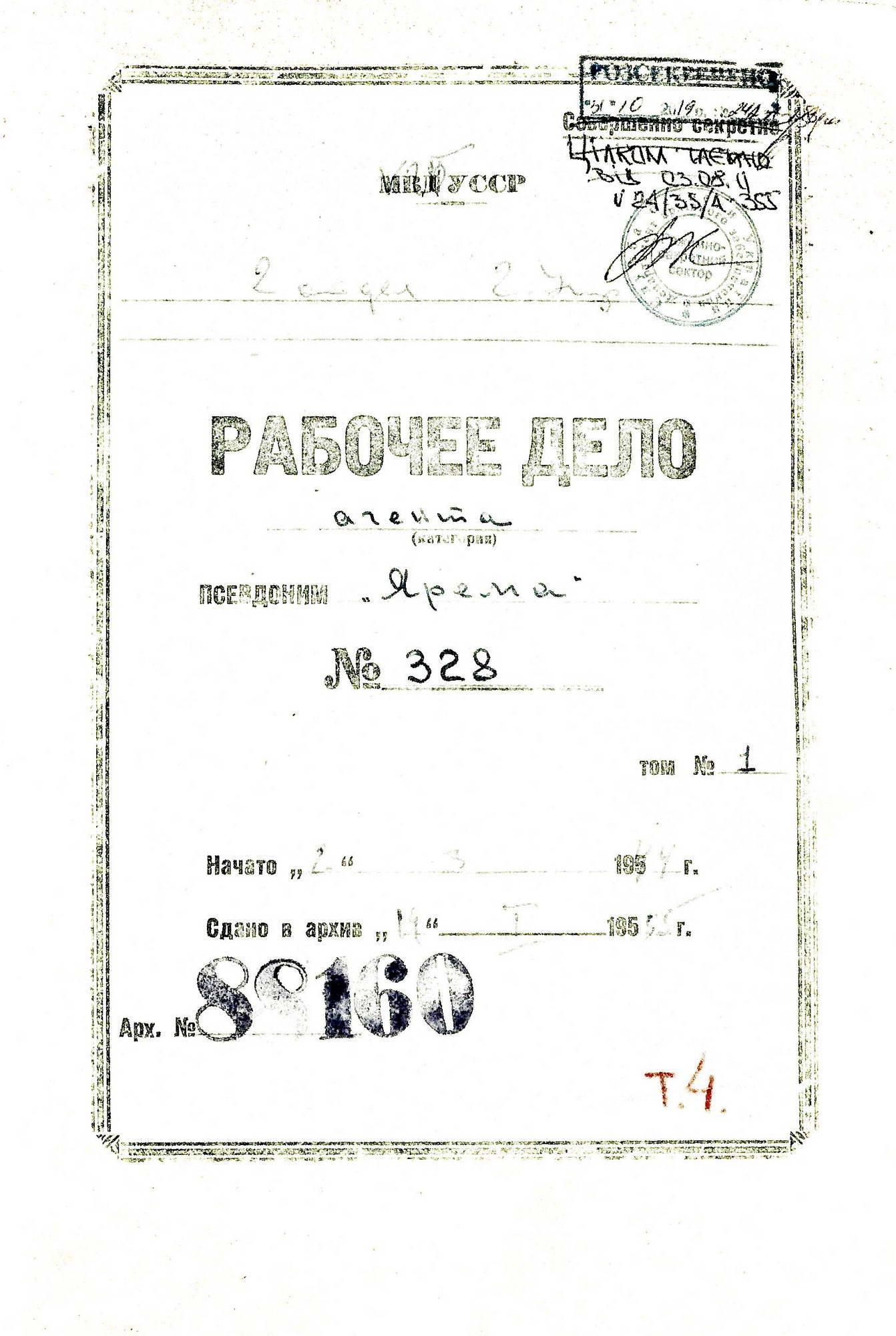

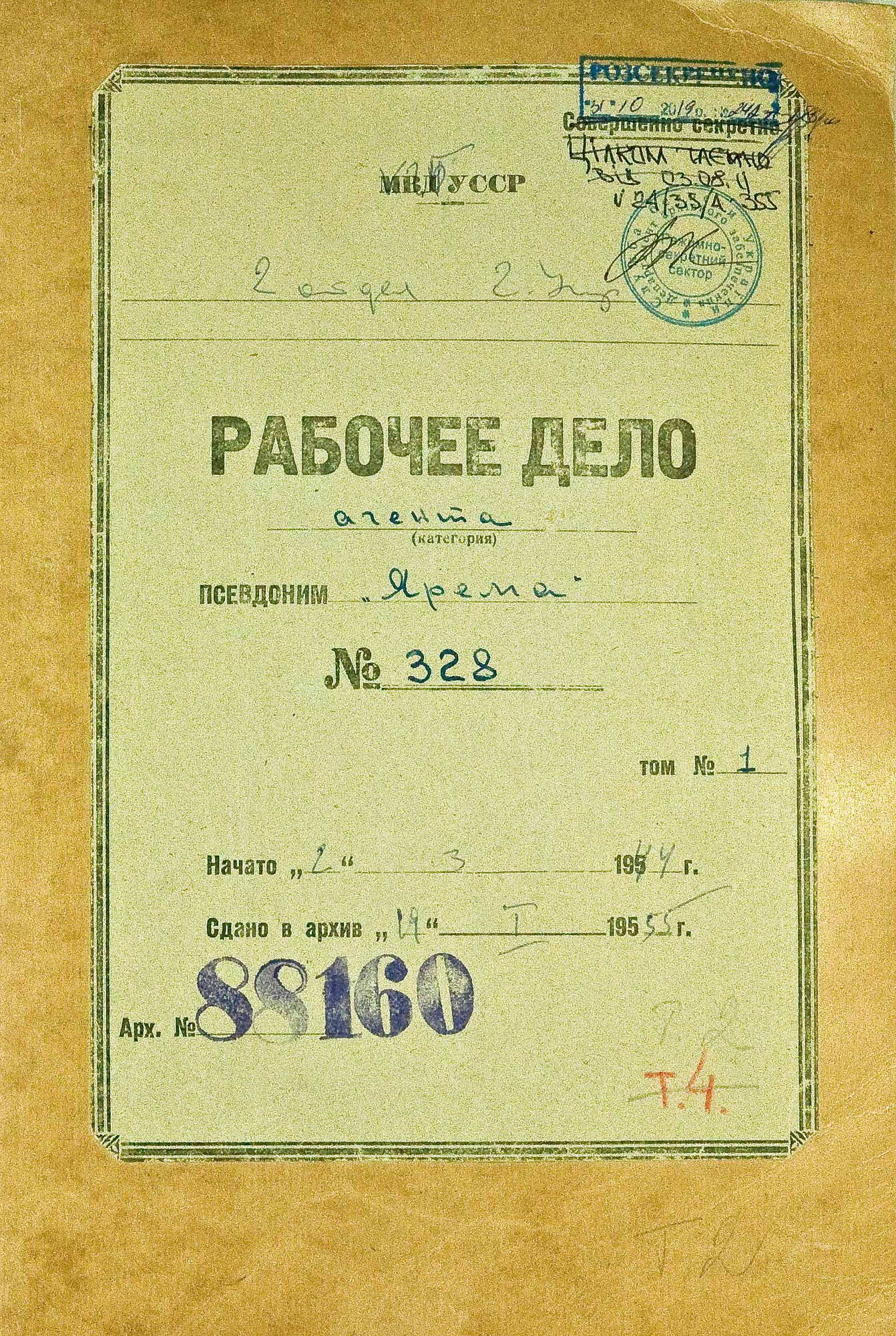

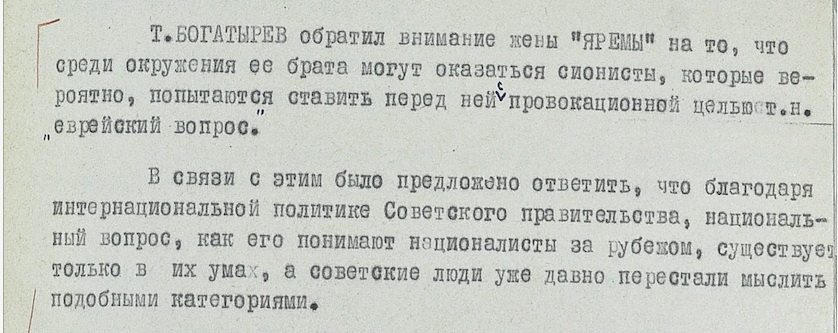

The cover of Yarema’s agent file. Source: SSU Archive

Yarema’s first task was to provide characteristics of people, whom he was in touch with and who might be of interest for further work. Soviet secret services, in particular, wanted to know, if Vasyl Vyshyvanyj had political plans for Ukraine. Hlushchenko was a frequent visitor at his house, but they reportedly discussed only art and books from the USSR.

Hlushchenko also told about Vynnychenko, who lived in Paris. They were in “the best friendly relations”. Vynnychenko had trust in him: they spent the whole summer together on an island. The documents say that in the 1920s the artist enjoyed Vynnychenko’s financial support. Former politician of the Ukrainian People’s Republic had a liking for the Soviet state and gave strategic advice to Hlushchenko: “not to rub shoulders with Ukrainian migrants to preserve the Soviet passport”.

The USSR was not interested in Vynnychenko, therefore the friendship was to be ended. “Vynnychenko is of no use. We don’t need him to return, he won’t become an agent. Our goal is to withdraw him from Hlushchenko’s influence and to ensure reporting we need instead of a friendly one”.

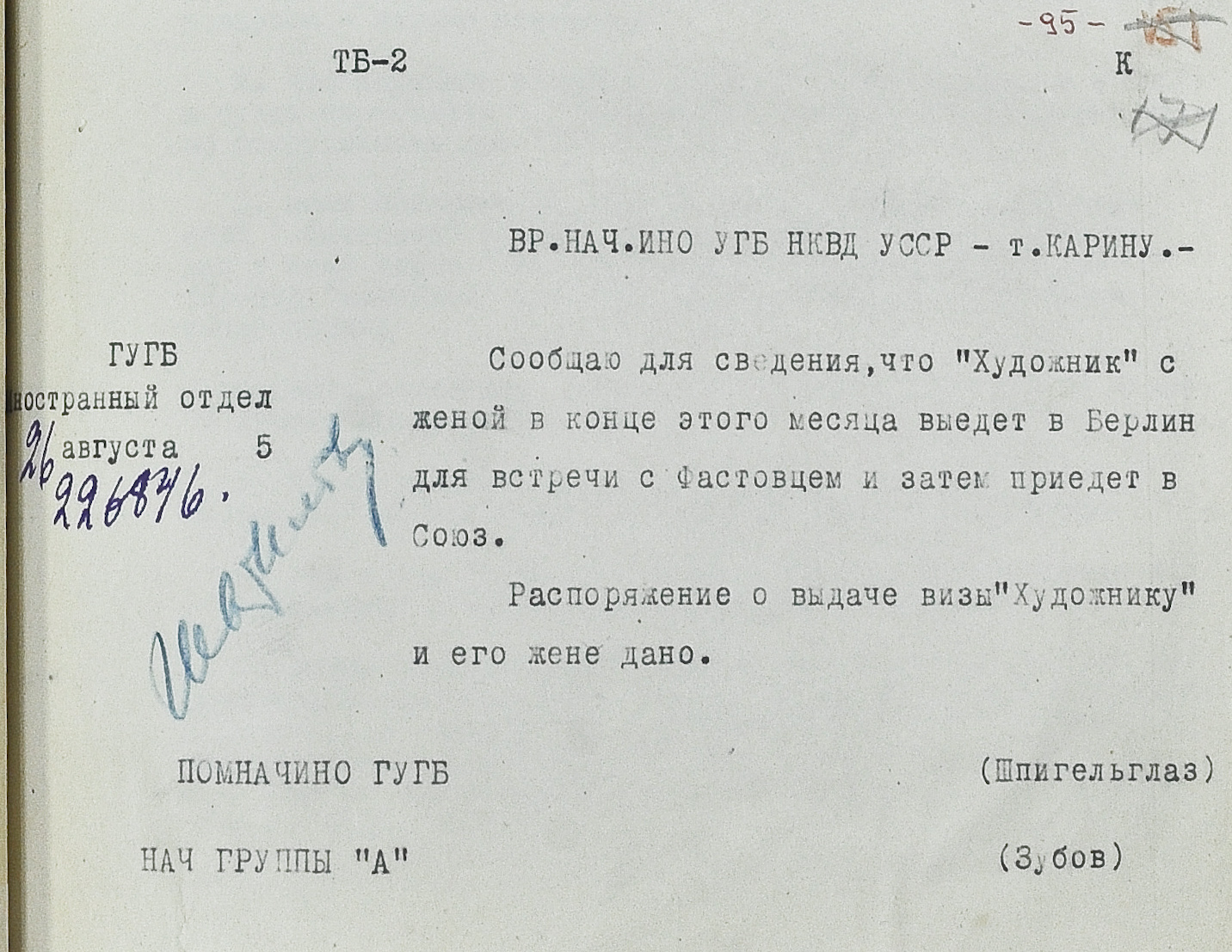

Leaving for the USSR

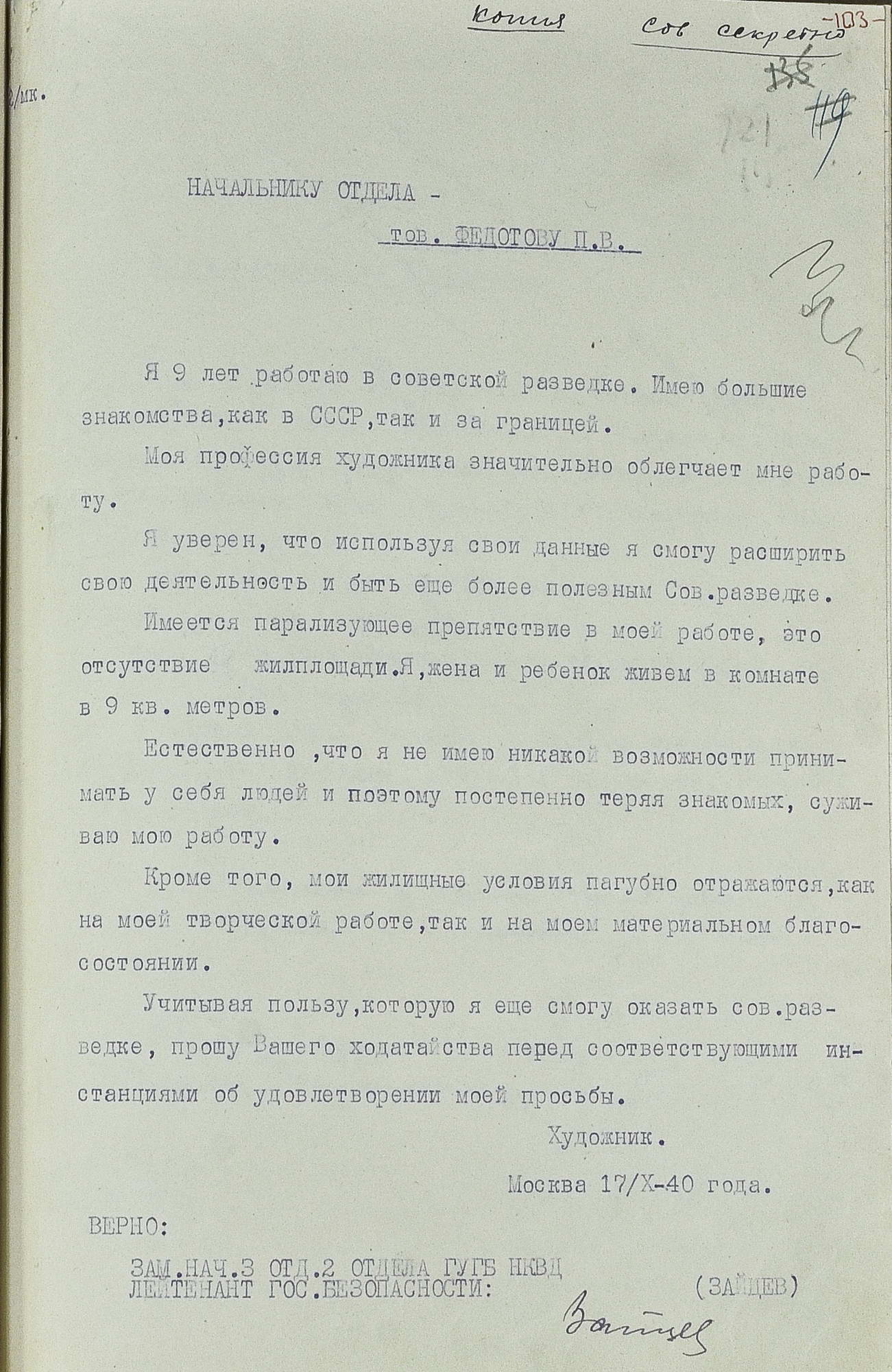

Letter about living conditions

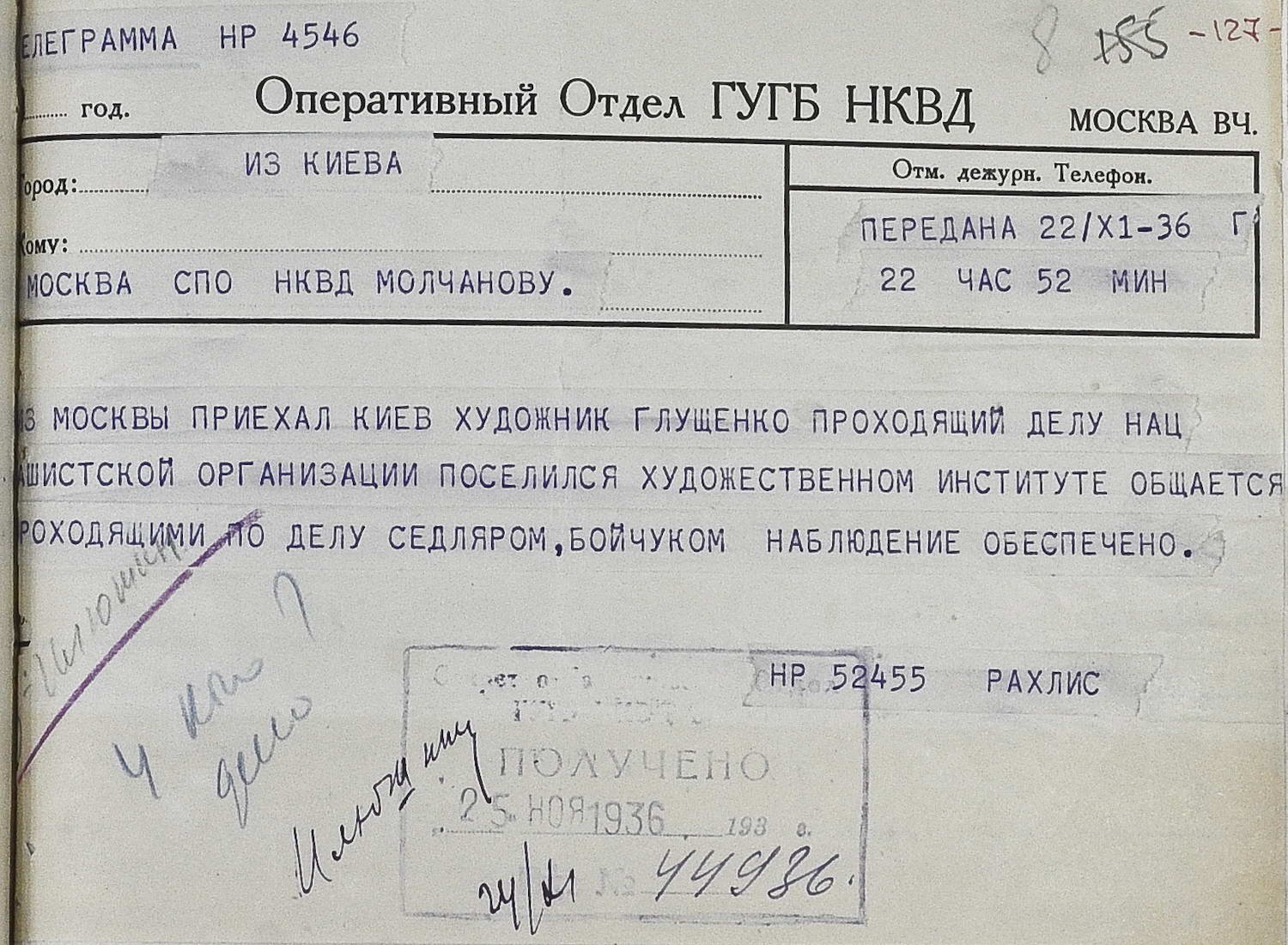

Ілюстрація 12 Telegram to Moscow

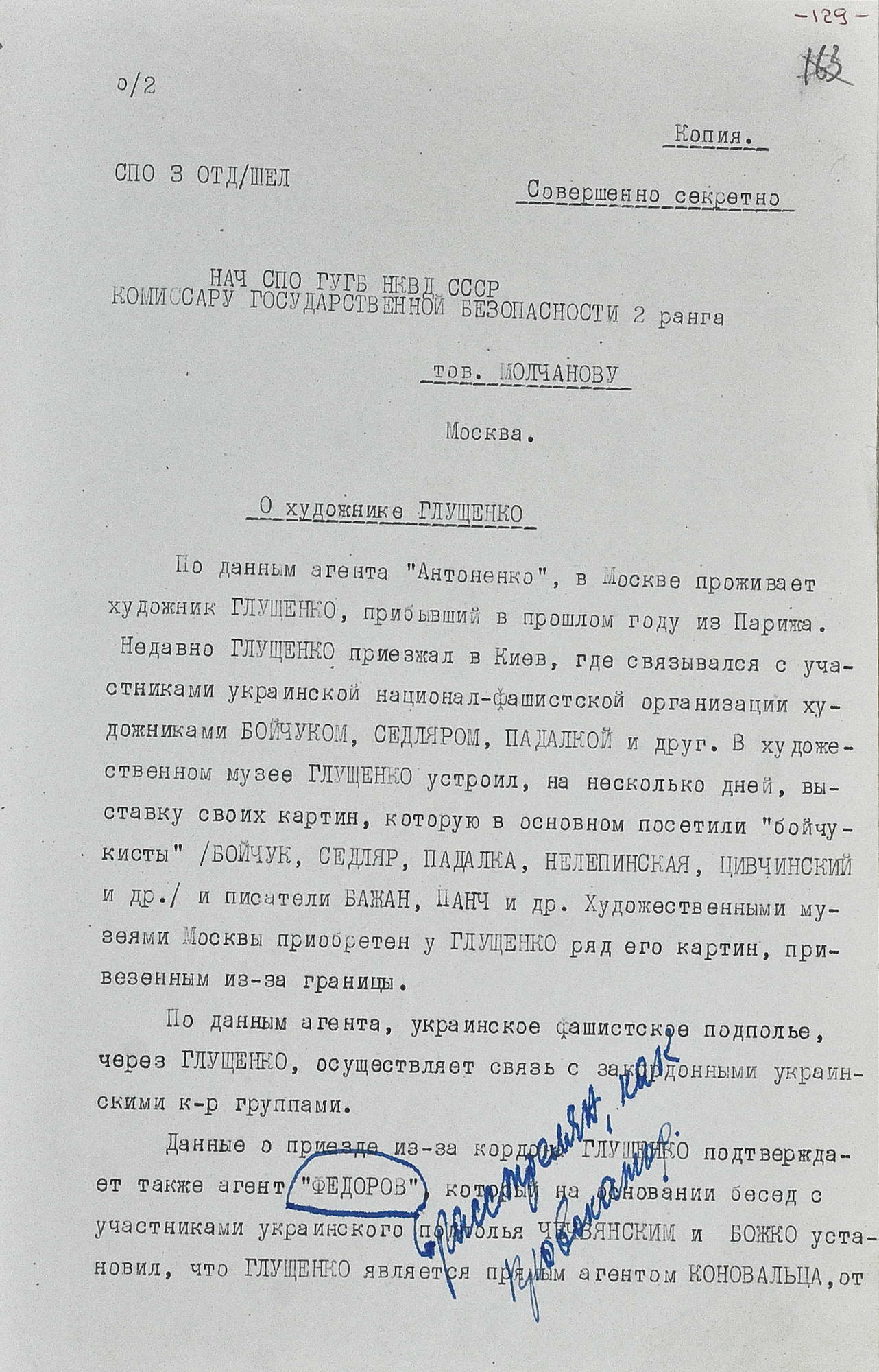

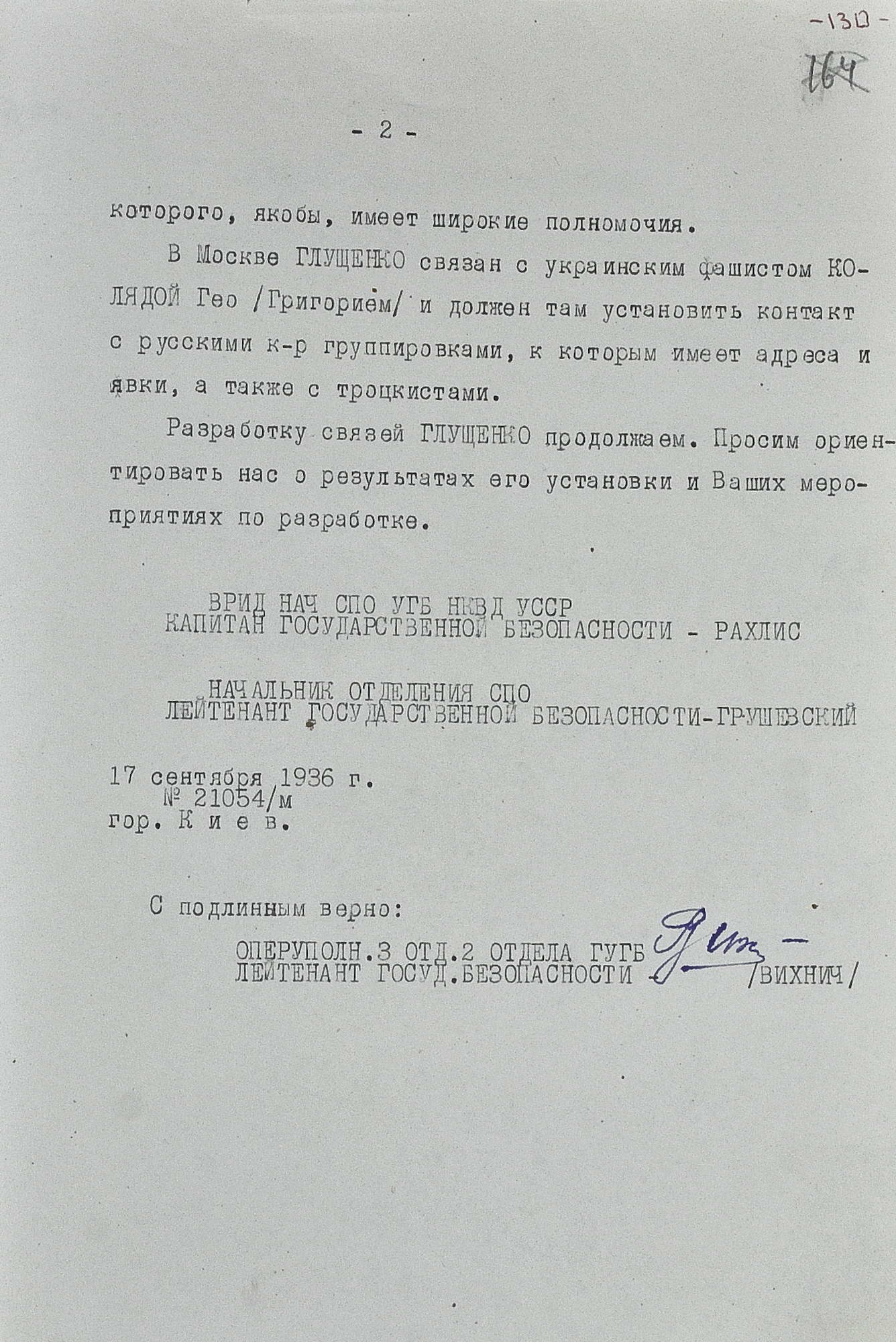

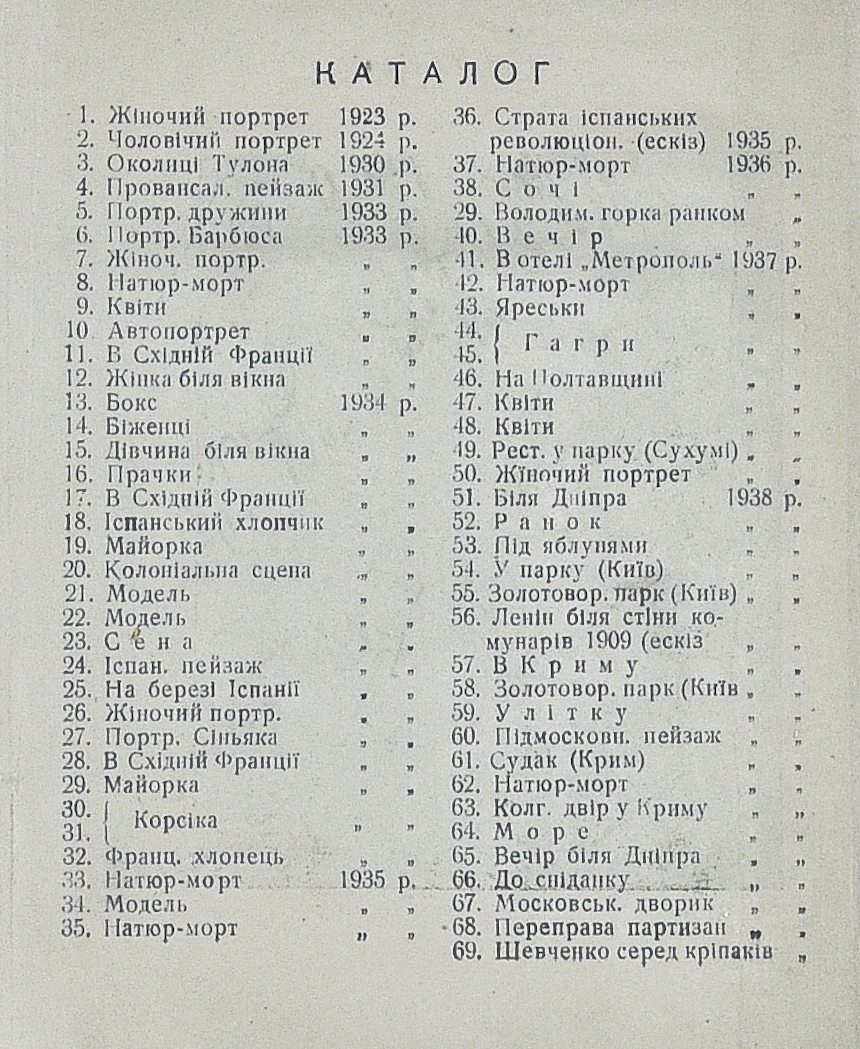

In September 1936, Hlushchenko organised an exhibition of his paintings in Kyiv Fine Art Museum. It was attended by Boychukists, namely Mykhailo Boychuk, Vasyl Sedlyar, Ivan Padalka, Sofia Nalepynska (all four would be executed the next year), Mykola Tsivchynsky and writers Mykola Bazhan, Petro Punch and others.

There is a circle around agent’s last name and a note “Shot dead as a provocateur”.

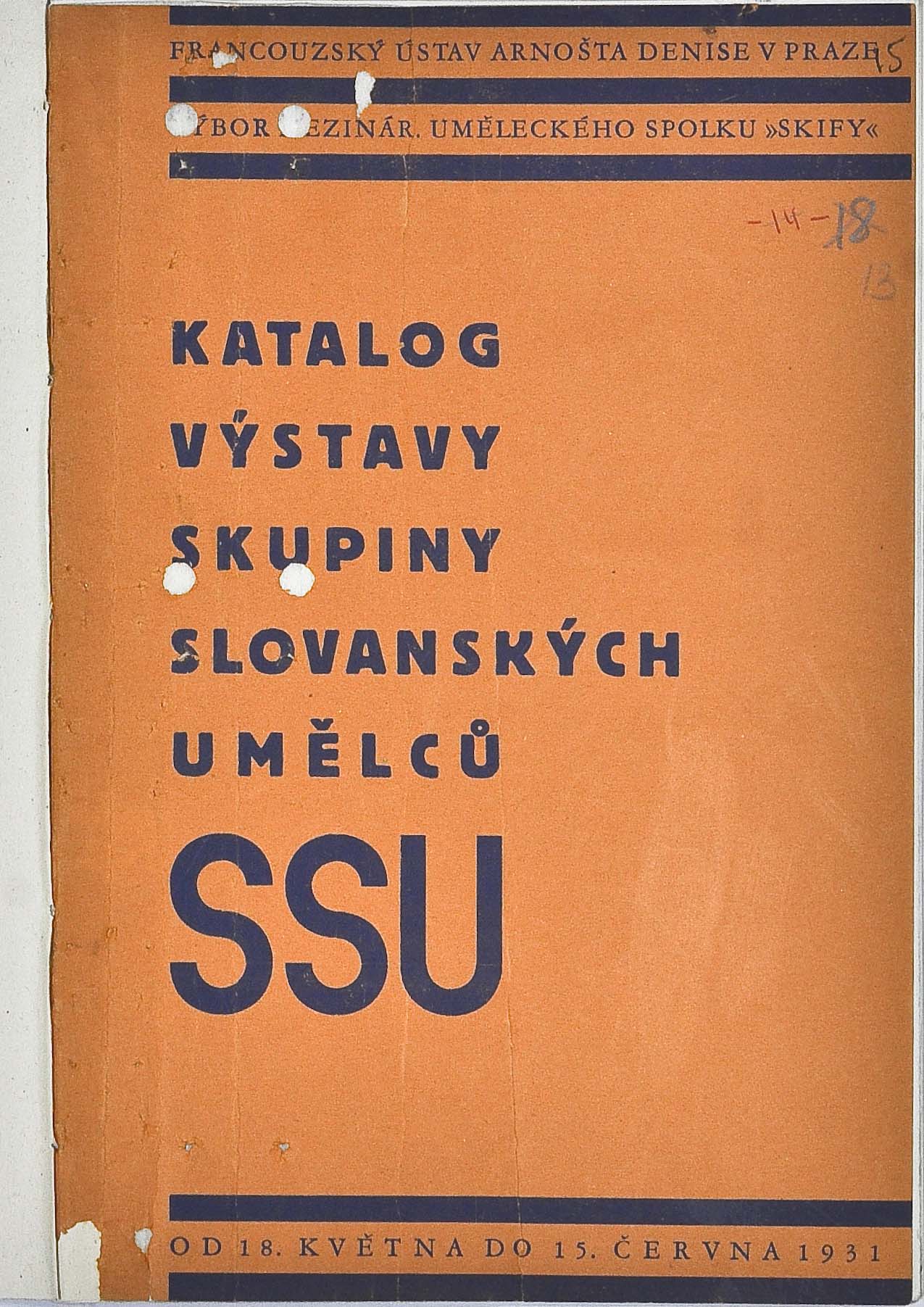

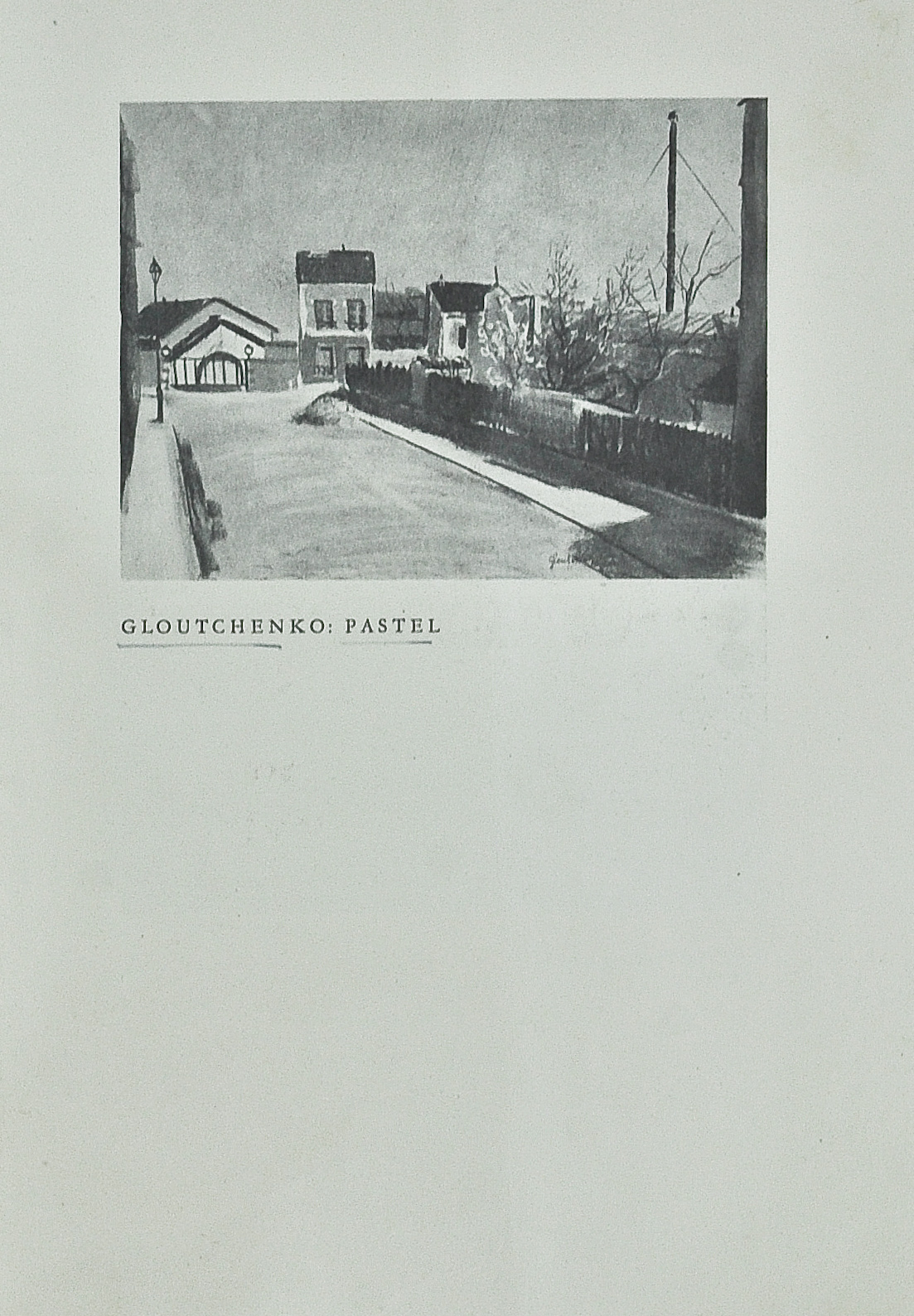

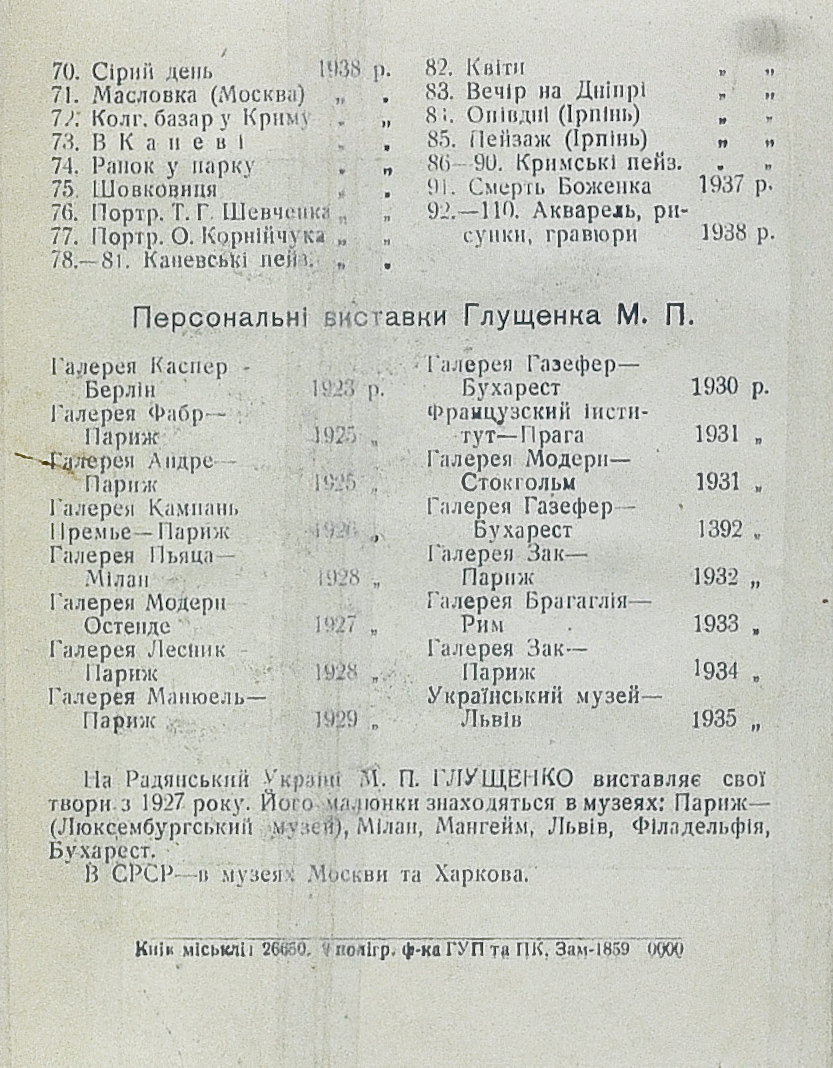

Hlushchenko’s catalogue and works

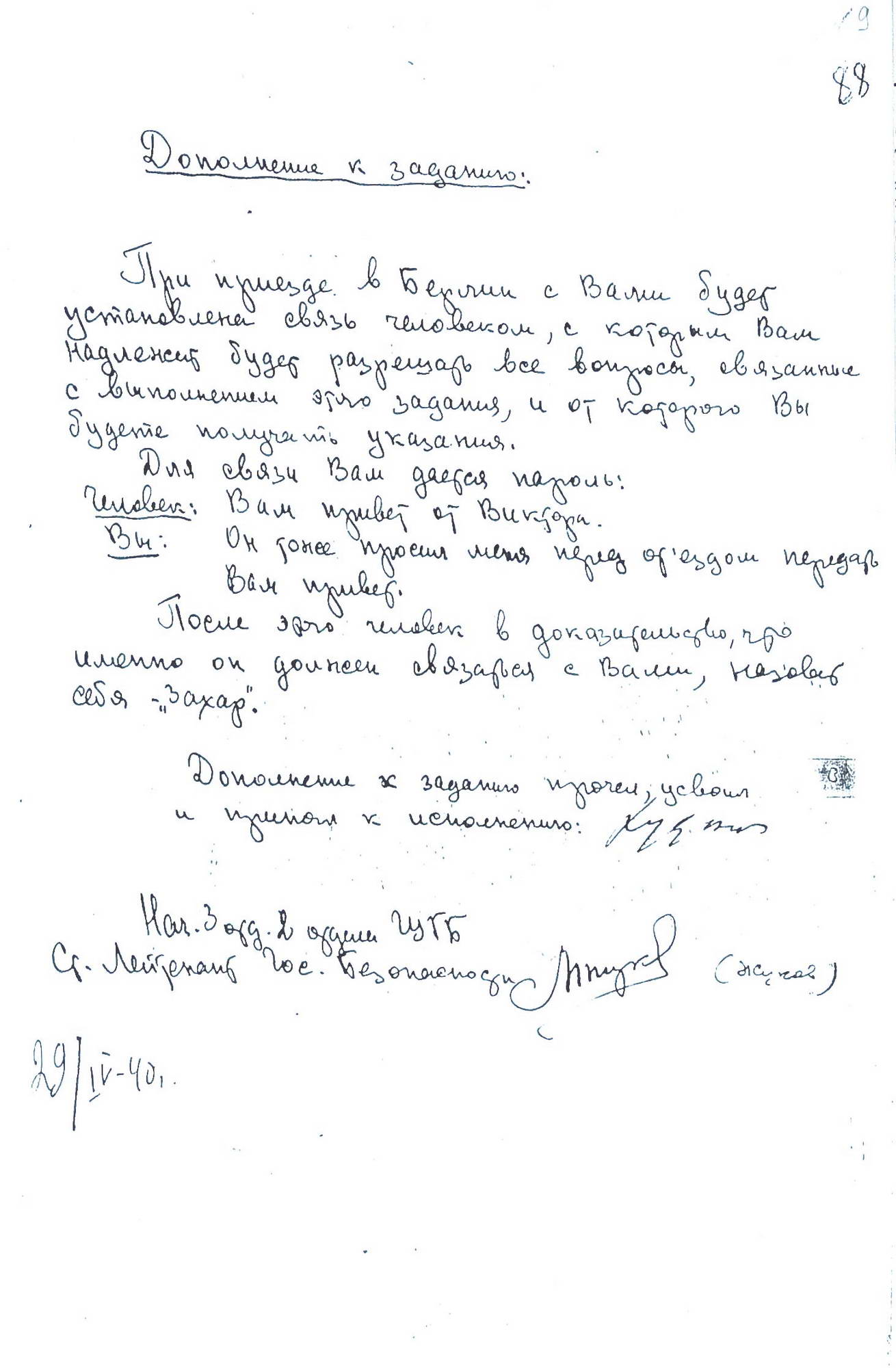

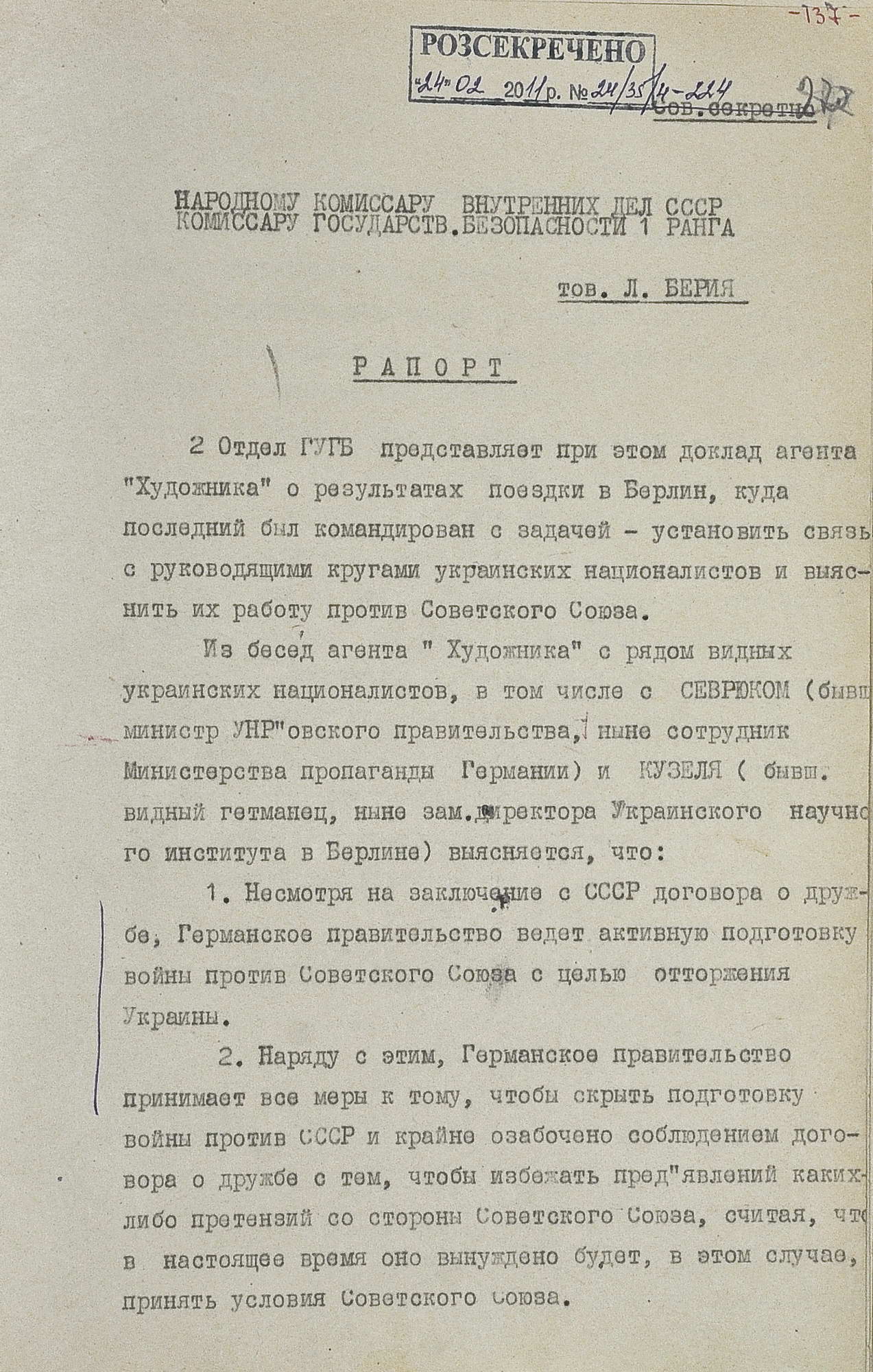

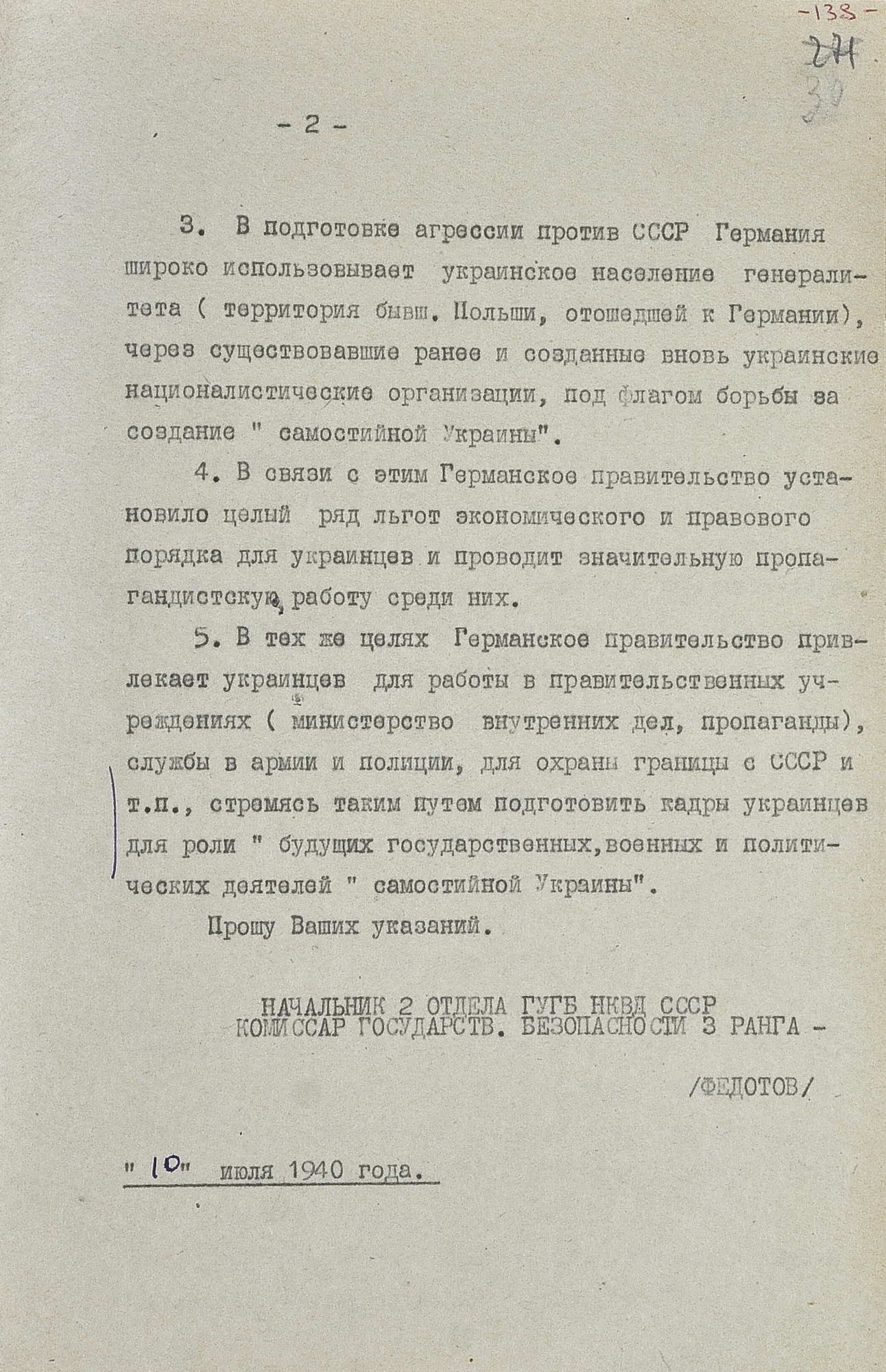

On 10 July 1940, Lavrentiy Beria, Molotov and Stalin were informed about results of Hlushchenko’s trip to Berlin, where he organised an exhibition on behalf of the USSR. His secret meetings and conversations with Ukrainian migrants, holding key public positions, revealed that Germany was actively preparing to war with the Soviet Union to “alienate Ukraine”.

The report on the Artist’s trip to Berlin submitted to Beria

In October 1940, when World War II was ongoing and Stalin and Hitler had divided Europe, agent Artist negotiated an exhibition of German artists in Moscow with Kleist, an officer from the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The official reason was to promote German art in the Soviet Union. However, the Germans promised Hlushchenko to organise his personal exhibition in Berlin.

Hlushchenko complained about poor quality of copies of German paintings, but the exhibition took place all the same, so that the agent could preserve contacts with valuable officials from the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Representatives of the German Embassy were invited to the closed event. Beria received a report about the event on 25 October 1940.

Ilya Braunstein

At the end of the war, the Hlushchenkos moved to Kyiv. Here “Yarema” became a lecturer at a university, met international delegations and retold conversations of Ukrainian artists to secret services.

His file shows that artist Hlushchenko sometimes prevailed over agent Hlushchenko. For instance, he noted that paintings of “artists of non-objective art”, like Marc Chagall or Wassily Kandinsky, were “kept in great numbers in basements of museums” in poor conditions. Apparently, Hlushchenko understood the value of the paintings and tried to save them by offering Soviet leaders to sell them to the West: “these are great assets and the Soviet state could get a lot of money for these paintings, the more so as museums don’t need them”. In the West, “prices for their paintings reach 8-10 million French francs”.

Sometimes he took note of tragicomic situations, for instance, when the administration in the hotel for foreign citizens Intourist hung paintings by German artists that had been taken from Germans during World War II or through reparations. Not only were some of those works of poor quality, but also such gestures puzzled visitors of the USSR.

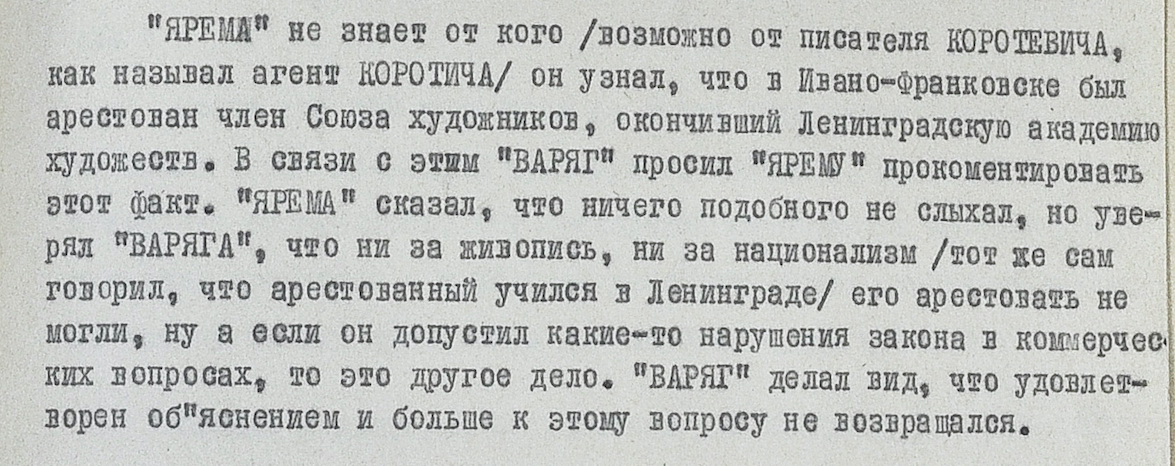

In 1960, artist’s wife also became an agent. Maria, a professional fashion designer was codenamed “the Female Artist”. Her task was to gather information about people of interest to intelligence, while visiting her brother in Brussels.

The KGB warned her that there might be Zionists in her brother’s environment, who would try to raise a “Jewish issue”. Maria was instructed to answer that “the national issue [..] exists only in their heads, while Soviet people stopped thinking in such terms long ago”.

If representatives of Ukrainian political organisations complained about Russification of Ukraine, she was to “show 1-2 newspapers in Ukrainian”. She was also advised to wrap some of the gifts for her brother in those newspapers, for them not to be considered a “propaganda material”, deliberately brought to Belgium.

In the 1960s, the internal contradictions between artist Hlushchenko and agent Hlushchenko deepened. He complained that officials lacked competence in art. “The Ministry of Culture, our only employer, represented by the Minister, often decides on its own, whether to accept [paintings] for an exhibition or sale, and sometimes a decision is biased”. He also lamented that the Ministry of Culture was cutting back on art purchases, and the paintings bought were of poor quality.

Hlushchenko emphasised that Ukrainian art was not allowed to show national identity. “The Baltic states, Armenia and Georgia have their own distinct national style and have obvious advantage over Ukraine, which resembles and follows Russia in its art. The Ministry of Culture or the Central Committee rejected everything more or less new and different from the commonly known art”.

He told that even when a painting was allowed to an exhibition, a representative of the Central Committee could remove it later on. “Exhibitions are stripped of everything controversial, unusual and new”. Officials explained that the people would not understand that. If artists started to argue, nobody bought their paintings at all.

Hlushchenko complained that lecturers at universities lacked knowledge and competence, so young people had nobody to look up to, while painters of “unique” portraits of Lenin, Stalin and Marx earned the most, although their works had no artistic value.

Tetyana Yablonska and the dog named Sharik. Late 1970s

“Drunkenness and strife flourish. The culture is low”, he used to say about artists, who refused to participate in the union work. “[..] Most artists don’t even attend exhibitions of their fellows and discussions, they gave up on everything. The awards, artists received at the Decade of the Central Committee of Art divided the collective even more, everybody feels left out, because some of the awards are incomprehensible indeed!”

“Yarema” complained that the youth started admiring the West, “got infected”, and did not approve of the Soviet control methods. He said that instead of punishing they should explain that conventional abstract art had been long gone.

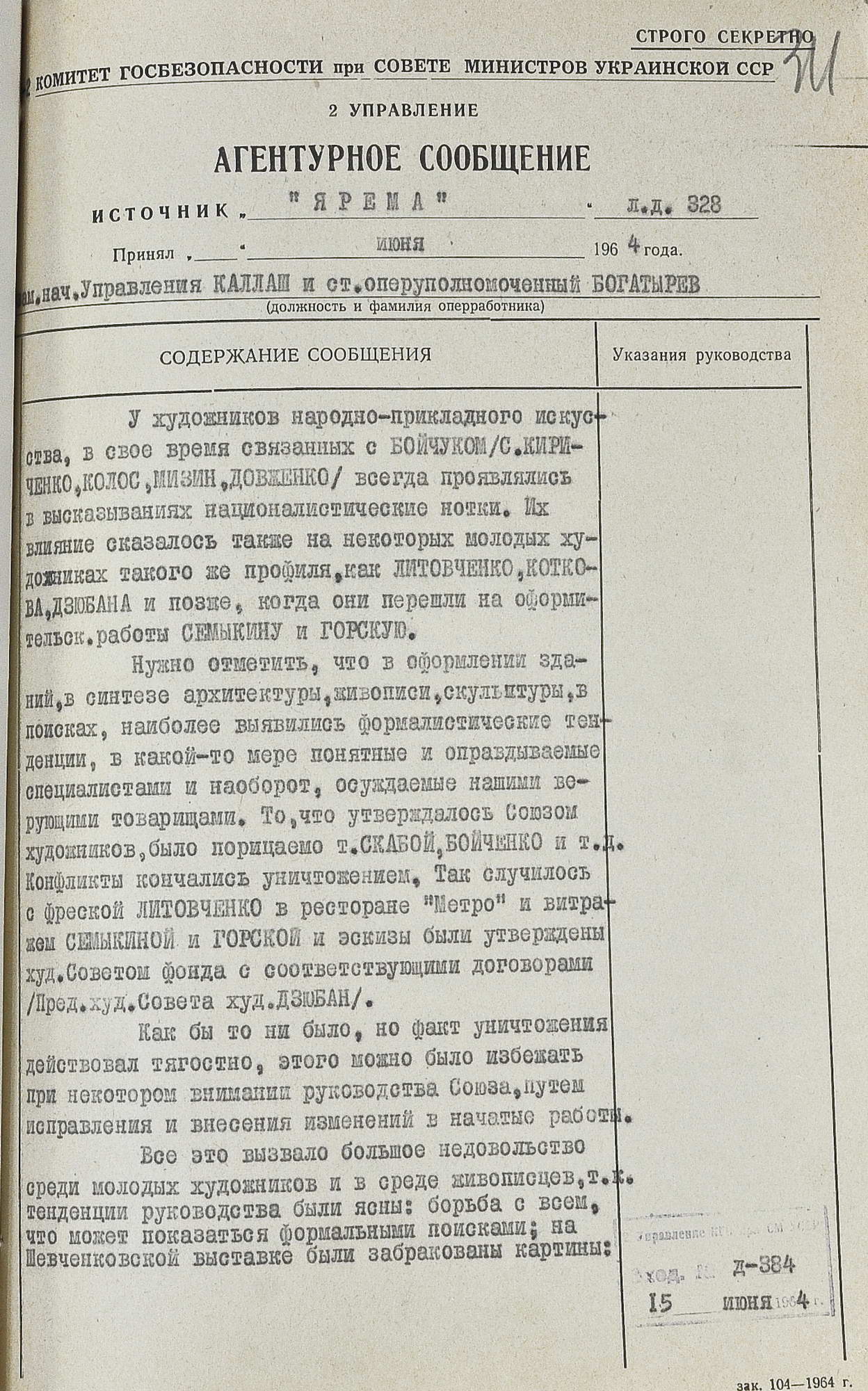

Hlushchenko did not support the destruction of the Sixtiers’ works, e.g. mosaics of Ivan Lytovchenko in Metro restaurant in Kyiv and stained glass panel of Lyudmyla Semykina and Alla Gorskaya (probably Shevchenko. Mother in Shevchenko University). According to him, authorities should not have approved sketches and signed contracts in the first place, since destruction only dejected artists. He also did not approve when artists were excluded from the Union, because that meant “giving them up to another influence”.

At the same time in 1964 Mykola Hlushchenko repined that the artists turn to “Ukrainian nationalism” and ⅘ of the artists don’t attend Spilka.

Criticizing stagnancy of the art life he didn’t do well in perceiving new ideas and faces. For several times his denunciations negatively mentioned, for example, monumental artist Ada Rybahcuk and Volodymyr Melnychenko, whose works the Soviet government would tag as “Boychukists” and eventually would destroy the project of their life they considered as the main - Memorial Wall at Baikove Cemetery. Hlushchenko admitted them as “very talented and hard-working people” but accused them of establishing opposition “between young and old” and total criticism. The artist called them “disputable” and “not admitting any authority”.

“They have forgotten elementary ethics, achievements of famous artists, and the meaning of art. It all came down to the unworthy dirty fudge with known results. The end of this decay are the elections of the board during the congress where [they tried to prevent — author] people who support the line of the party from getting to the Board”.

“Yarema” himself stayed as non-partisan and for youth it created an aura of confidence and authority which he always complained to have a lack of. In 1966 young artists-Sixties even tried to persuade him to stand as candidate for the Chairman of the Board of the National Union of Artists of Ukraine.

Ukrainian and Armenian film director Serhiy Paradhzanov in Tbilisi

On the arest of Opanas Zalyvakha

In 1975-1976 Hlushchenko went to France to work for several months. At the same time the French media extensively published about the violation of human rights in the USSR, particularly as “Yarema” reported “they have launched a loud campaign around the mediocre dissidents that originated from the USSR”. At the same time Leonid Plush came to France after compulsory psychiatric care in the USSR and termination of his Soviet citizenship. Hlushchenko called the dissident as a person “full of void and unworthiness” as “he has left their motherland”.

He also complained that the Soviet media work with the image of the Soviet Union inefficiently. Also Western countries were indignated with Solzhenitsyn’s “Gulag Archipelago”. “Yarema” admitted to having read it: “I have a grieved impression. The episodes described in detail are obviously made-up and depictured in gloomy and ominous tones. In general this is a boring garbage born in the sick imagination of a despitefully anti-Soviet author”.

Till the end of his life Hlushchenko conducted active agent work. The last denunciation is dated 24 August 1977. He died of cancer in 2 months, on 31 October. The KGB and party leadership attended the funeral ceremony.

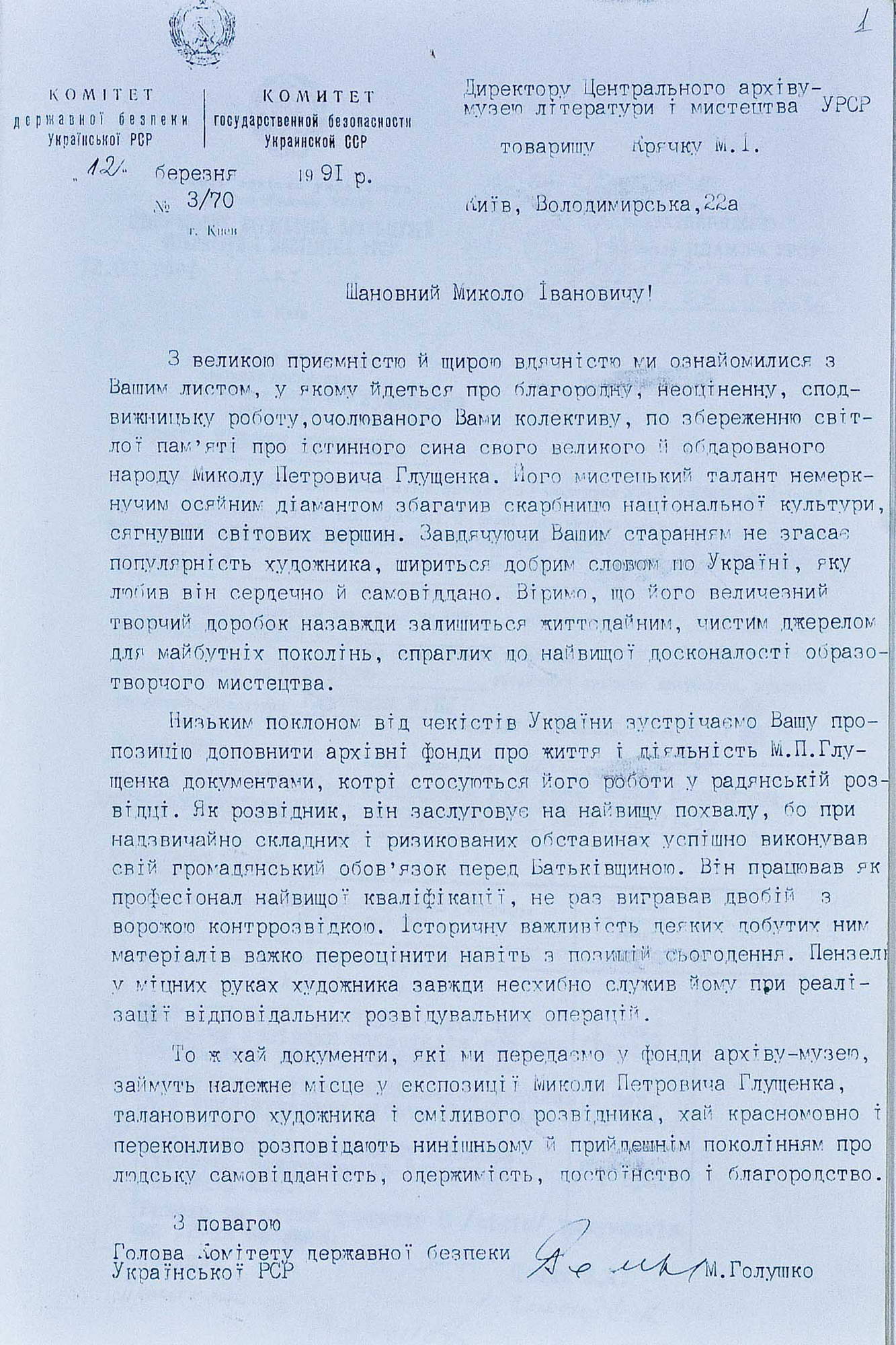

“With the deepest gratitude on behalf of the chekists of Ukraine we welcome your request to complement the archive fund about the life and work of Mykola Hlushchenko with documents concerning his work in Soviet intelligence. As an intelligence operative he deserves the highest praise for executing his civil duty to the Motherland in outstandingly difficult and risky circumstances.

[...]

So let these documents [...] eloquently and persuasively demonstrate real dedication, obsession, dignity and nobility to the current and following generations”.

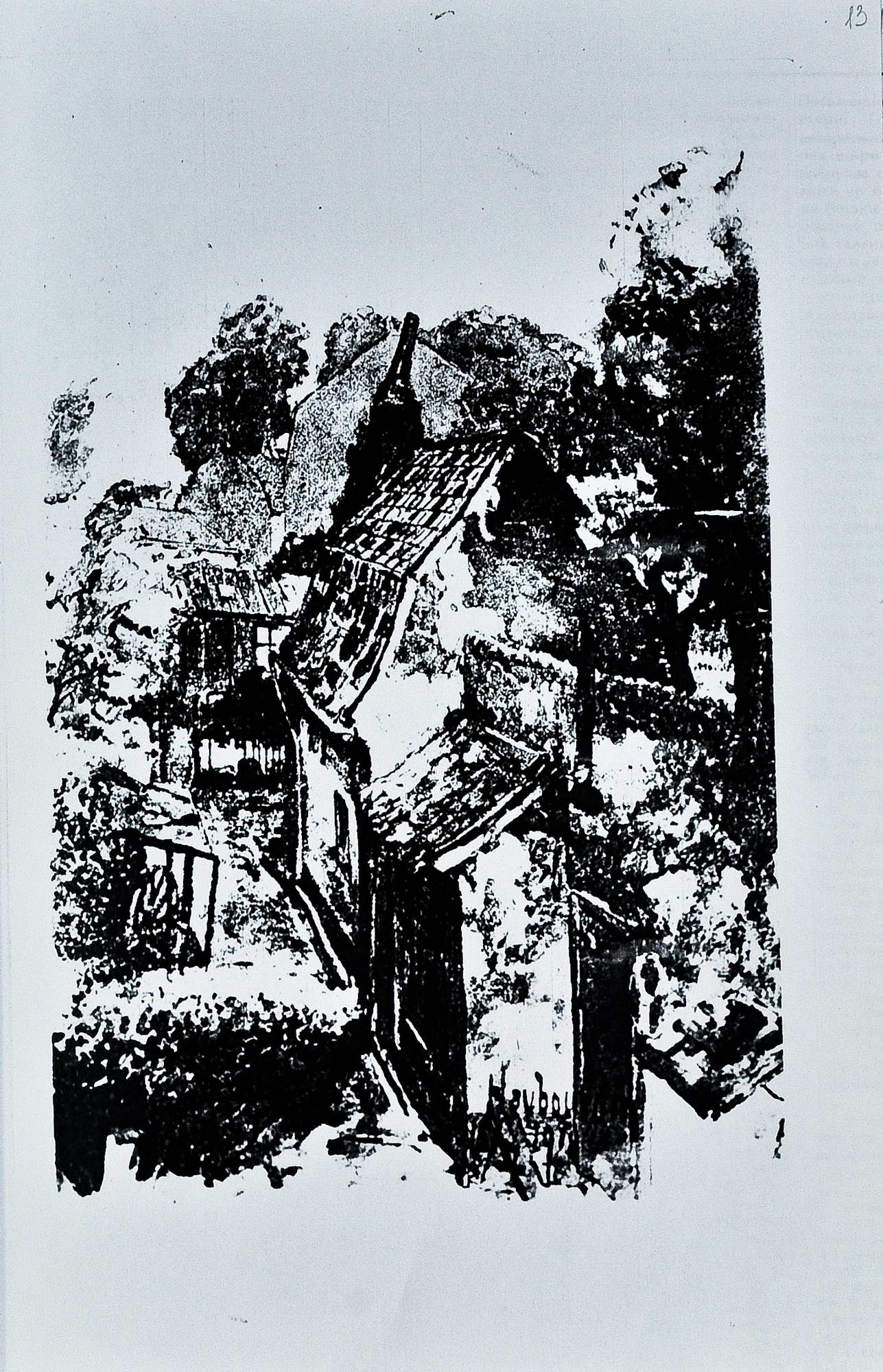

Adolph Hitler's watercolor from the album presented to Glushchenko