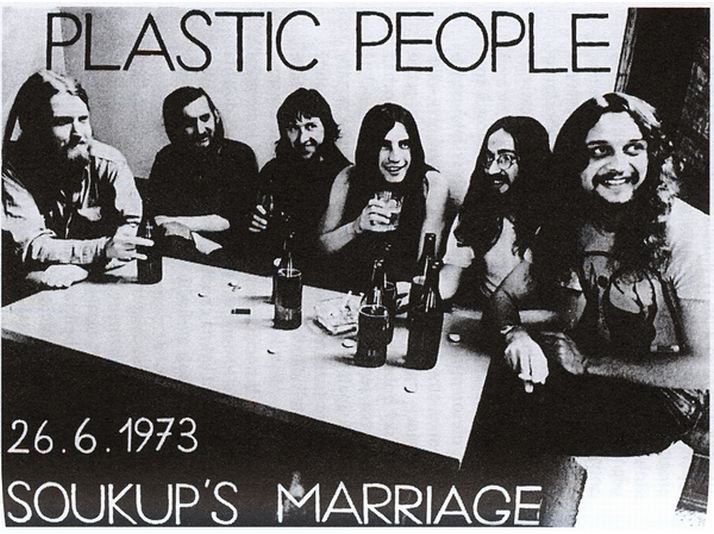

The Plastic People

of the Universe

rock band

1968

|

1988

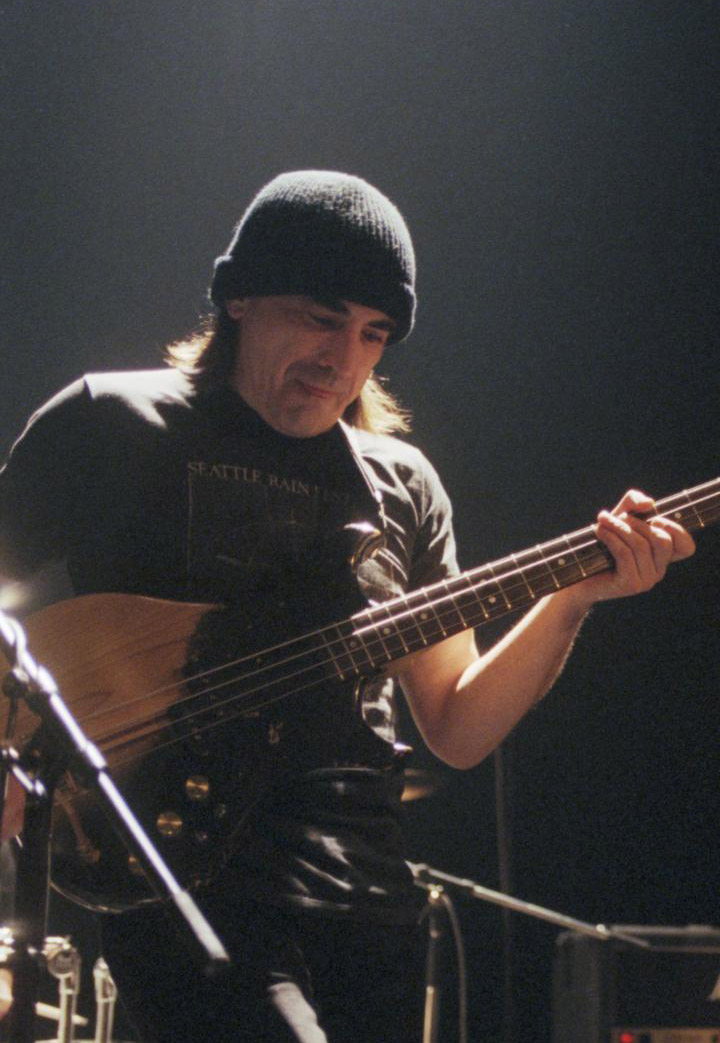

The Plastic People of the Universe was a Prague rock band and one of the prime movers in the Czechoslovak underground movements between 1968 and 1988, inspiring the formation of many other underground groups. Milan Hlavsa founded the band in 1968, and Vratislav Brabenec, Josef Janíček and Jiří Kabeš were its core members in the 1970s.

The band found itself in opposition to the communist regime in Czechoslovakia in the 1970s and 1980s, and its non-conformist performances caused it to suffer from persecution and imprisonment.

StB referred to independent musicians from the underground and rock milieu as “longhairs”. Young people whose conduct and appearance did not fit in with the normalisation culture in Czechoslovakia were the target of both propaganda campaigns and direct persecution.

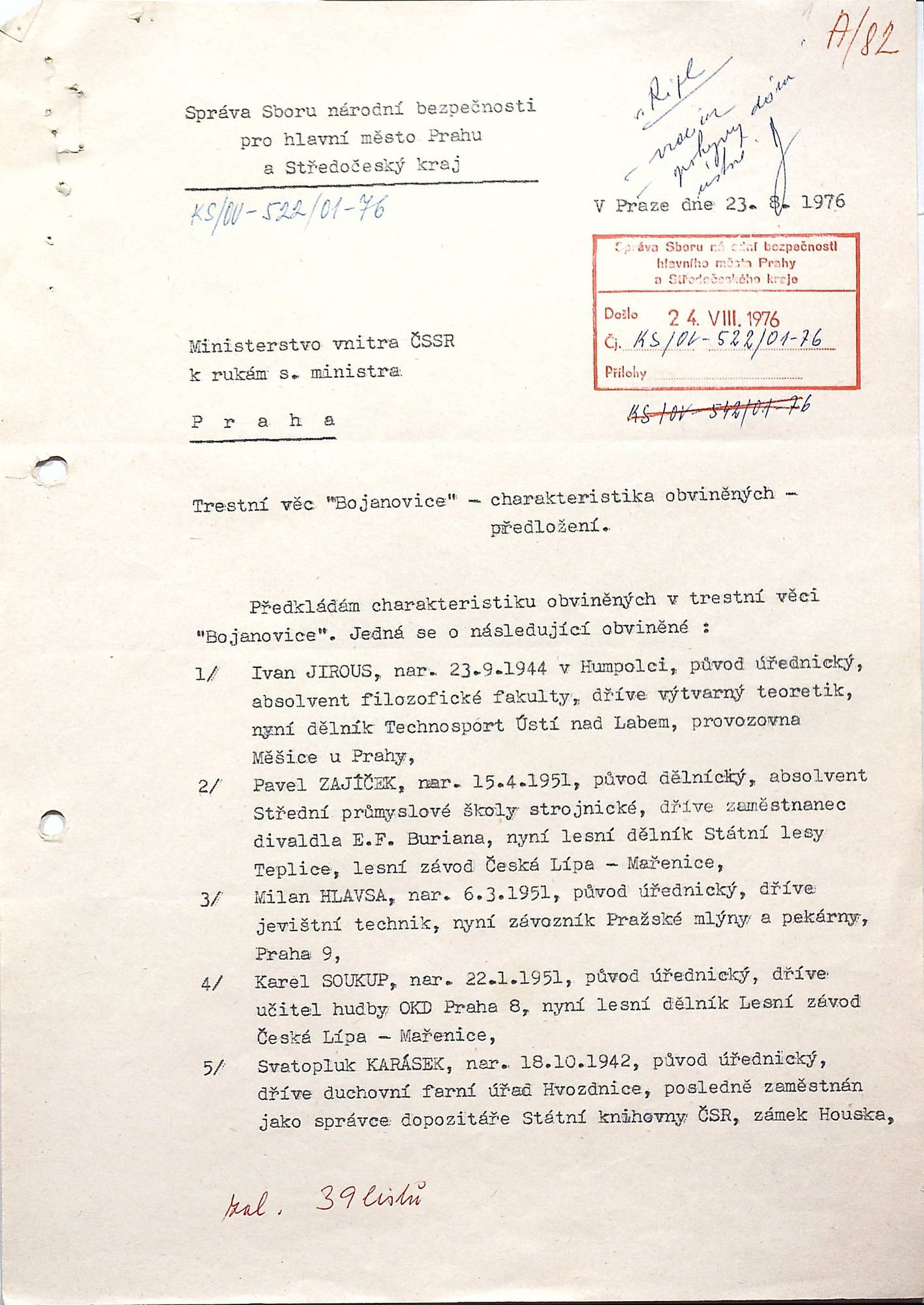

Ivan Martin Jirous AKA “Magor”, a cult figure of the Czechoslovak underground movement, the Plastic People’s art director and the author of the Notes on the Third Czech Musical Revival essay from 1975, which was also published abroad, was in prison several times. This was not only on the grounds of his cultural activities, but also due to his eccentric behaviour.

From November 1975 on, StB persecuted underground musicians under a nationally directed project with the cover name of “Kapela” (Band). The PPU were denied the status of professional musicians in 1973, which virtually robbed them of opportunities to perform legally in public.

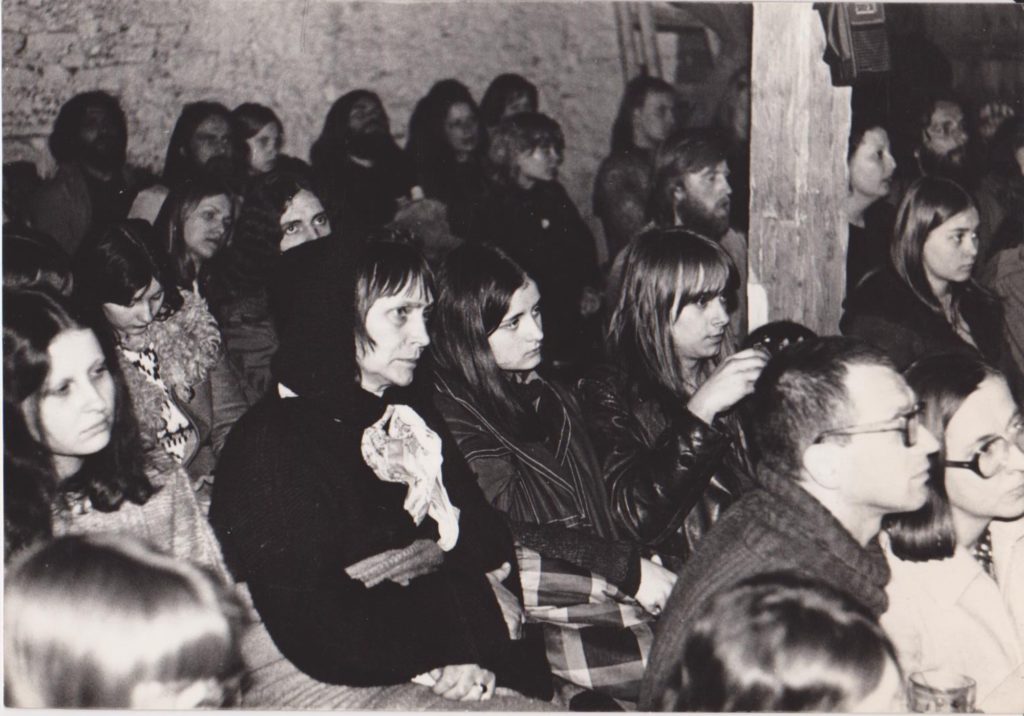

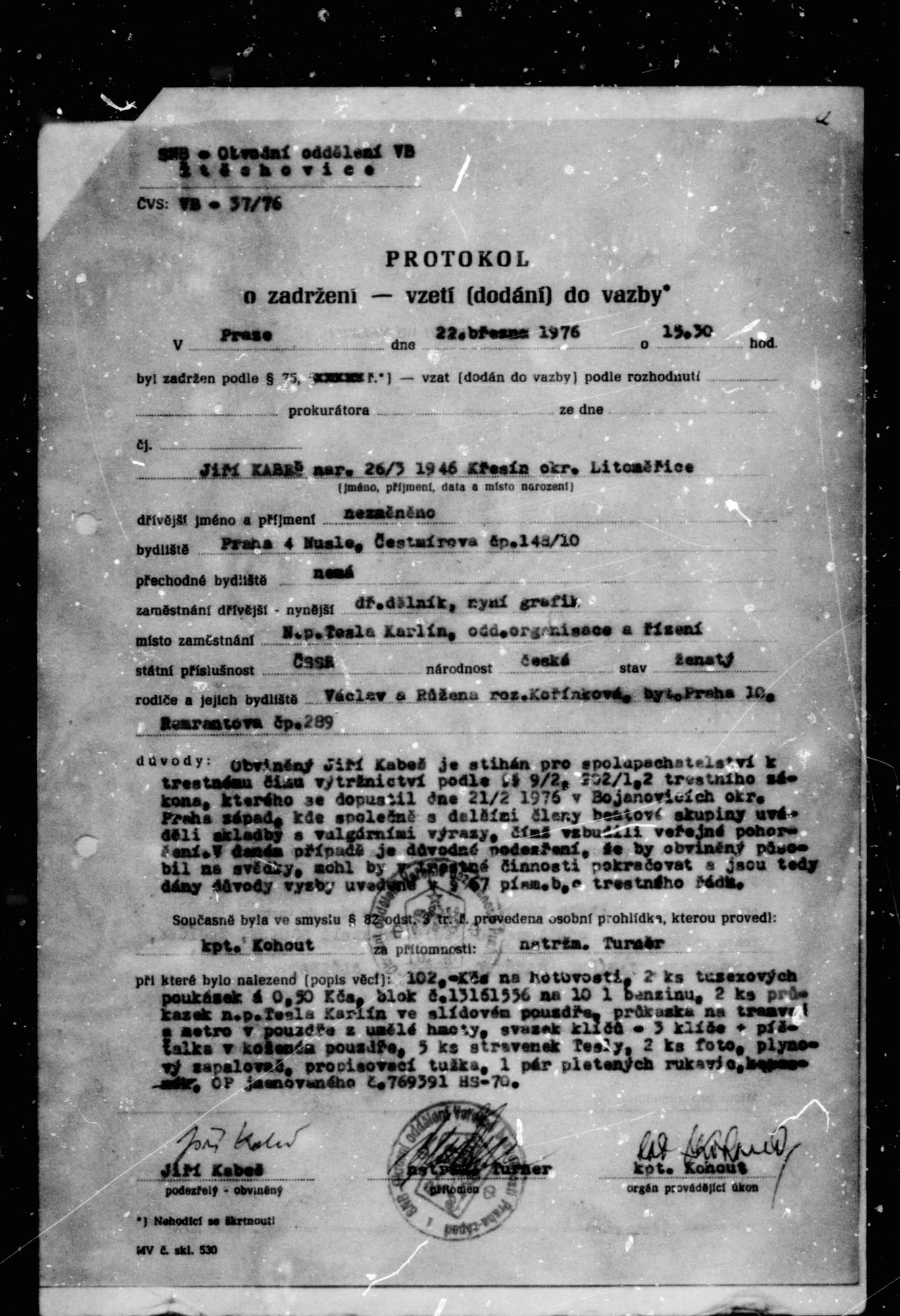

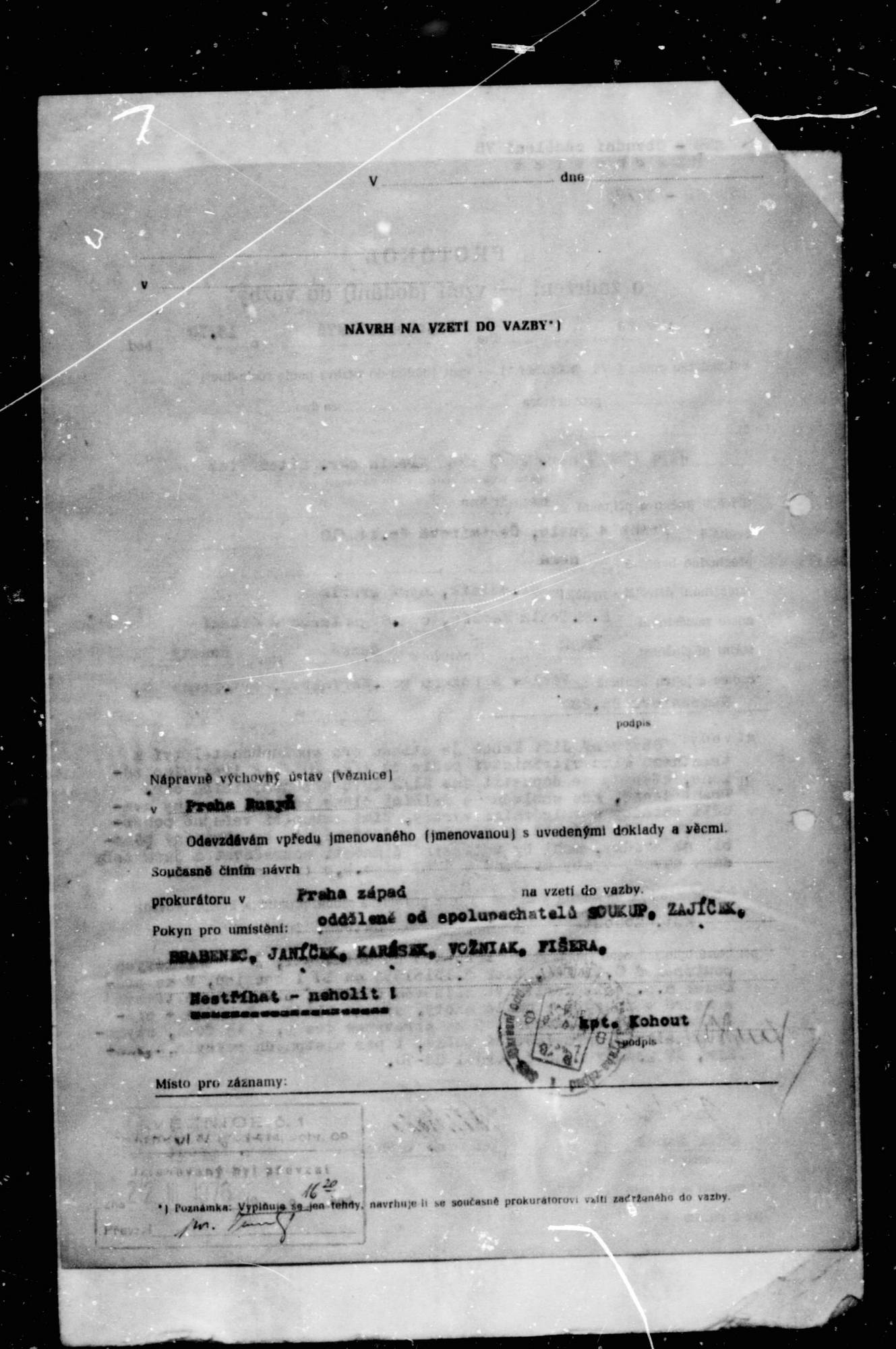

Attended by some 400 young people and featuring other groups in addition to PPU, an unofficial concert was held in Bojanovice near Prague in February 1976 on the occasion of Ivan Martin Jirous’ wedding. In response to the event, StB raided the participants and arrested over twenty people including the members of The Plastic People of the Universe.

Many popular personalities spoke out in defence of the young musicians, including poet Jaroslav Seifert, philosopher Jan Patočka and writers Václav Havel, Ivan Klíma and Pavel Kohout.

The involvement of popular personalities of Czech culture helped the trial to gain media exposure, although the communication between intellectuals and the underground was not easy initially. Václav Havel once remembered his early liaisons with Martin Jirous as follows: “All I got were the occasional, somewhat wild, and as it turned out later, severely distorted messages about a community that he formed and called the underground, and about the Plastic People, an unorthodox rock band that was the core of the community and that Jirous was the art director of. As I heard from my friend Sněhulák, Jirous’ opinion of me was not very flattering either: to him, I was a member of the official and officially tolerated opposition ― i.e., in fact, the establishment.”

After meeting Jirous and hearing the Plastic People’s records, Havel concluded that it was a “deeply authentic expression of the feeling of life of people crushed by the misery of this world, disturbing with its musical magic”.

It was also thanks to the exposure of the anticipated trial in Western media that most of those arrested were released afterwards. Still, four people were sentenced to imprisonment with finality in September 1976: Ivan Martin Jirous for 18 months and Vratislav Brabenec for eight months. Svatopluk Karásek and Pavel Zajíček were sentenced along with them.

The “Plastic People Trial”, as it is commonly referred to, was an important impulse for the rise of the human rights movement in Czechoslovakia and, subsequently, for the writing of the key document of Czech dissidents, the Declaration of Charter 77, which united various groups of the rising dissident movement, from the underground all the way to Catholic intellectuals. Václav Havel described the process as follows: “The spectrum was complete, and even though it cannot be seen directly in the signatures on the various petitions, in reality it was exactly at this time that, in closer or looser connection with the Plastic People case, the principal groups that had hitherto been more or less isolated and that represented the core of the future Charter 77, came together and united informally, through various newly formed contacts and friendships.”

Once released, the band members were persecuted again. They were laid off from their jobs, were not allowed to perform in public, and StB would regularly summon them for interrogations and placed them in “preventive detention”.

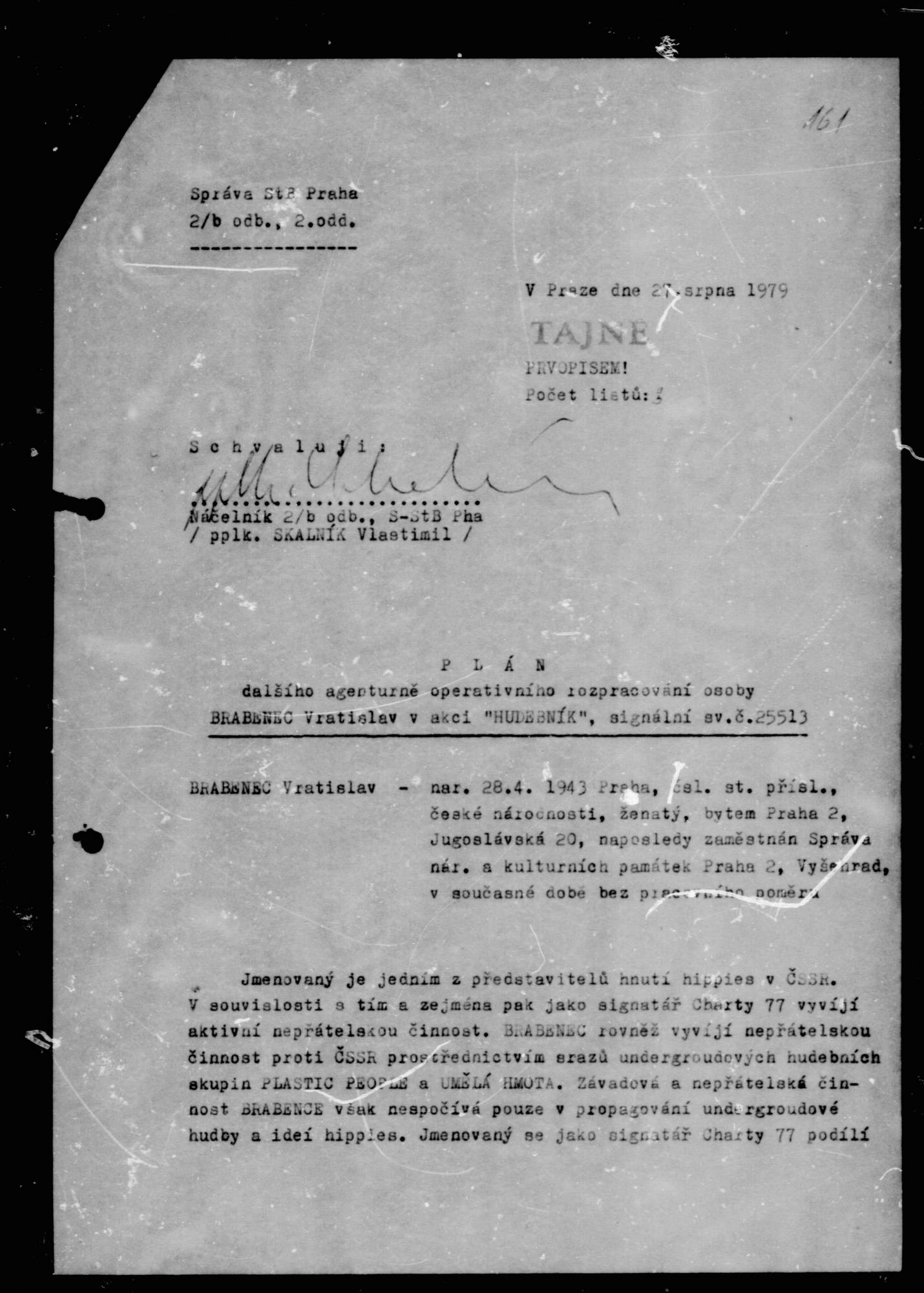

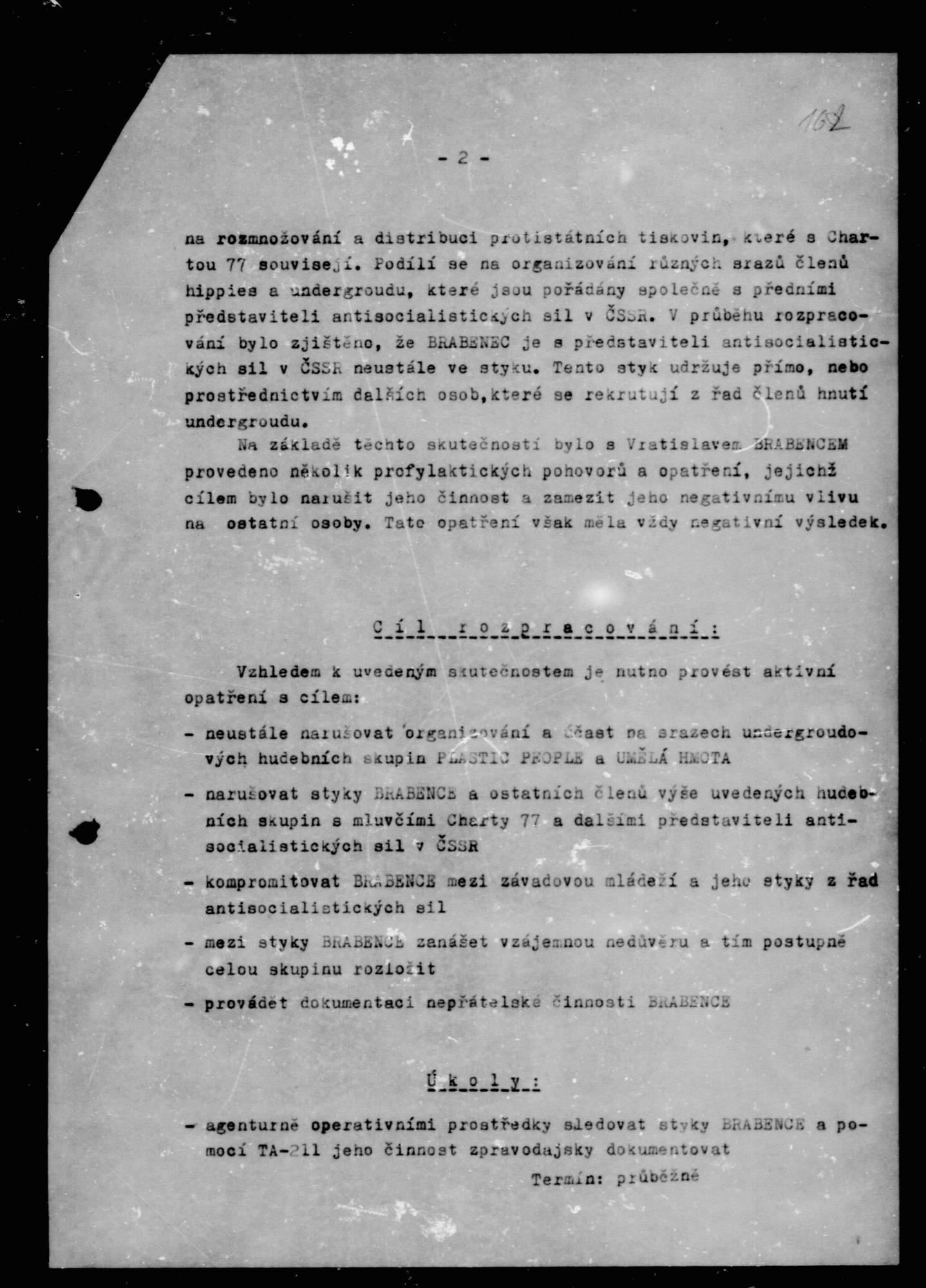

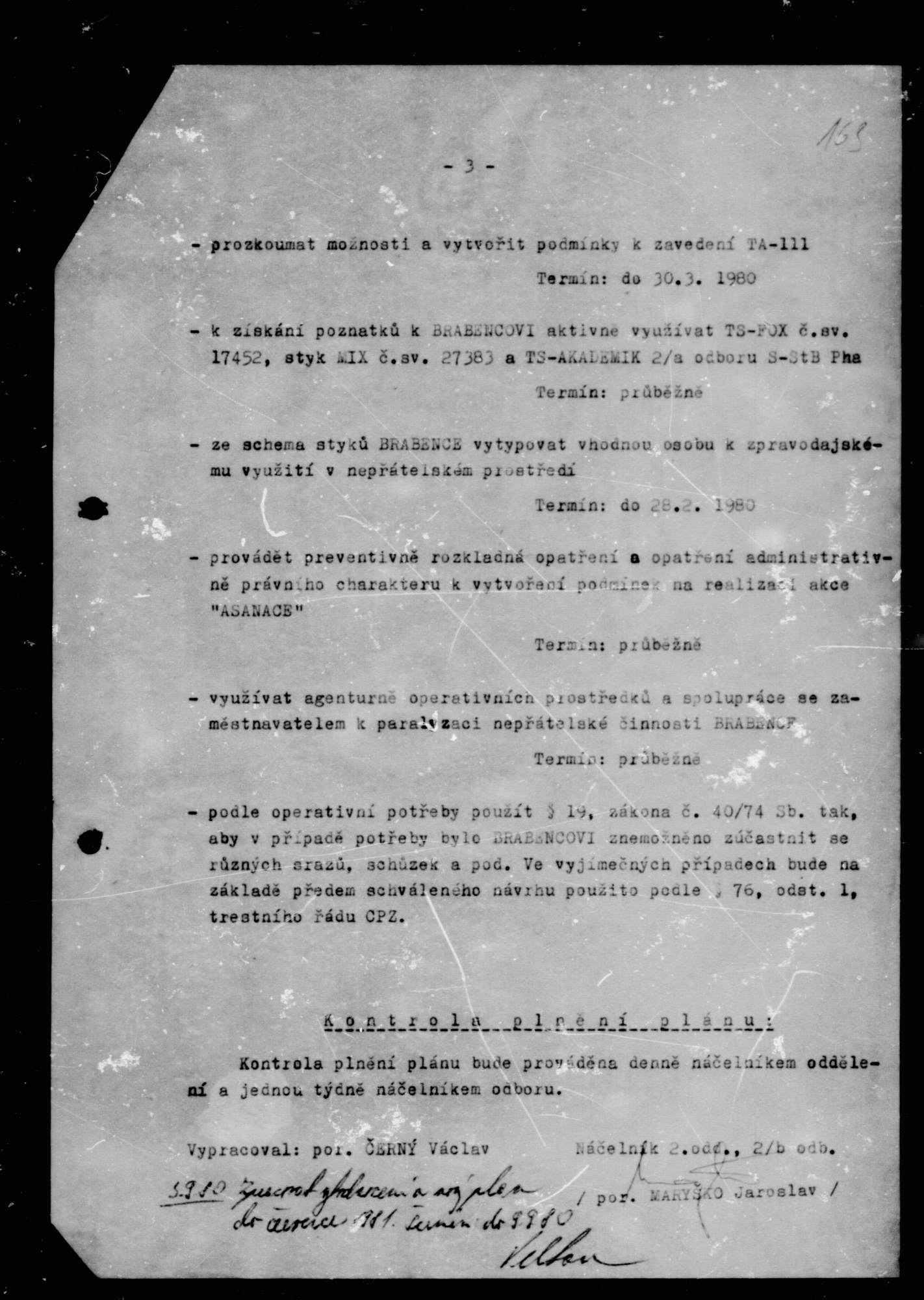

According to StB, Vratislav Brabenec’s hostile activity was allegedly as follows:

“As a Charter 77 signatory, the above named is involved in the dissemination and distribution of anti-government print related to the Charter. He participates in organising various hippie and underground meetings along with the leading representatives of antisocialist cliques in Czechoslovakia. It was found during the monitoring that BRABENEC is constantly in touch with the representatives of antisocialist circles in Czechoslovakia.”

Eventually, the musician was forced to leave Czechoslovakia in 1982 as part of StB’s Asanace project.