Overtaken by the communist party shortly after the end of World War II, Czechoslovakia experienced many dramatic turns in the latter half of the 20th century. Following a brief period of political pluralism in the initial post-war years, a communist coup took place in 1948; the local communists grabbed power and held it until the Velvet Revolution of 1989.

The communist rule made State Security (Státní bezpečnost, “StB”), founded in 1945, one of the key authorities. Over time, this organisation, similar to the Soviet KGB, took up the major repression duties in the country. The early 1950s in Czechoslovakia were marked by a wave of repression aimed against various opposing tendencies and “hostile elements”: the Roman Catholic church, the kulaks and political opponents.

The best-known victims of the show trials, staged following the model of the major ‘court trials’ in the USSR on the 1930s, include lawyer Milada Horáková and Rudolf Slánský, First Secretary of the communist party’s Central Committee. The liberalisation in the USSR that went hand in hand with Khrushchev’s post-1956 “thaw” had its opponents in Czechoslovakia for a long time. The 1960s, however, were a period of relative freedom in particular for artists and culminated with the Prague Spring, an attempt at “socialism with a human face”.

Following the invasion in August 1968, the country’s cultural life sank into a period of “normalisation” – the rule of the official culture and socialist realism, punishing non-conformist artists. The works by many artists and writers were forbidden in the early 1970s. The release of the Declaration of Charter 77 was a major impetus for the forming of alternative culture; its core signatories were the backbone of the Czechoslovak dissident scene and the “unofficial” culture environment.

Nearly all writers and artists involved in activities related to Charter 77 were persecuted. StB used various methods of oppressing independent culture: propaganda campaigns (the ‘Anticharter’), forced emigration (project ‘Asanace’ (Sanitation)), home searches, wiretapping, arrests and physical abuse: all of that became part of the everyday life for Czechoslovak artists, writers and intellectuals. When the government archives opened for the general public following the Velvet Revolution, it paved the way for the detailed mapping of the persecution methods that the authorities used to exert pressure on non-conformist artists.

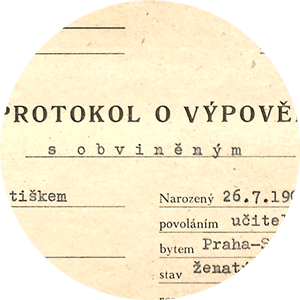

The documents and letters produced by the communist regime’s security forces are deposited in the Security Services Archive. A selection of 100 archive documents demonstrates the persecution of artists in former Czechoslovakia between 1948 and 1989. The greatest portion of material stored in the Archive involves the personal files of security service members and employees. This type of archive material is represented by the documents concerning StB member Jaroslav Vokurka who took part in persecuting graphic artist and painter Oldřich Kulhánek.

Investigation files represent an extensive and important corpus of archive material. An investigation file is a set of documents, photographs and other archival material that shows how a person was monitored before the arrest and when in detention. StB investigation files are immensely valuable archival sources in terms of both history and human rights. Surviving investigation files illustrate how StB acted against oppositionists. It is necessary to keep in mind, however, that when assessing files primarily from the 1950s, it is not plausible to simply accept facts without a critical approach to the historical sources.

Investigation often shows many signs typical of fabricated trials, in particular the physically and mentally demanding detention, intentional misinterpretation of the accused persons’ statements, stylistic alteration of the interrogation records by the prosecution authorities and use of illegal provocation methods. An important type of archive material that illustrates extensive terrorising is the files of the Ministry of the Interior Inspectorate from the 1960s when the communist regime showed a certain deal of self-reflection and attempted, at least to a certain extent, to investigate the most brutal cases of persecution.

The most desirable type of archive material from the researchers’ point of view are the secret collaborator and counterintelligence files. Secret collaborator files gather written documents, photographs and other archive material on persons selected for collaboration with StB or those who already undertook to collaborate. The files were kept in various categories defining the degree of collaboration, if any, as well as the degree of the candidate’s or collaborator’s awareness of being a collaborator. Counterintelligence files document the monitoring and/or persecution of persons or groups of persons. The files were kept in various categories that defined the scope and method of monitoring and persecution.

Even though StB attempted to destroy the majority of its written documents in December 1989, it actually managed to shred just a small part of the material. As a result, the Security Services Archive currently manages 748 archive collections containing almost 20,000 running metres of archive material, which, save for a few small exceptions, is accessible to researchers.